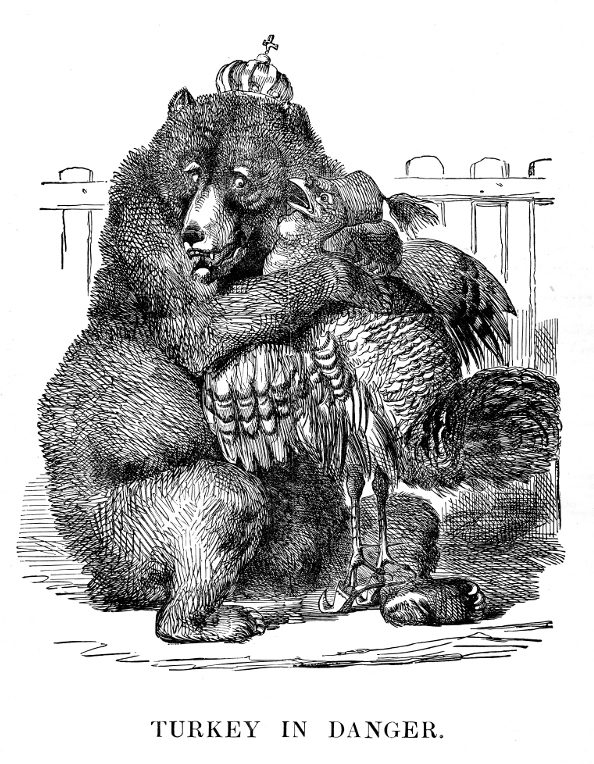

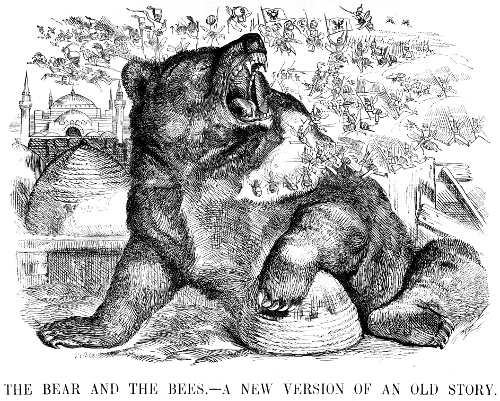

The Russian ‘bear’ embraces Turkey, centre of the Ottoman Empire. Nicholas I, the Tsar, had been speculating for some time about a partition of the Ottoman Empire. Britain and France greatly feared Russia would seize Turkey and force Christian Orthodoxy on its European neighbours.

CRIMEAN RELICS

An exhibition exploring aspects of the Crimean War through items held in the BRLSI collection. Satirical cartoons from Punch magazines bring themes from the war to life.

The causes of the Crimean War (1854–1856) were complicated and varied. Russia, under Tsar Nicholas I, provoked a declaration of war by Turkey, the centre of the Ottoman Empire. Russia had occupied areas under Ottoman control in an effort to force political concessions from the Turks, particularly in regard to the governance of Orthodox Christian populations under Ottoman rule.

Russia expected support from Britain, France, Prussia, and Austria, but European fears of an expanding Russian Empire led to increasing political tension and eventually war.

A Failure of Democracy

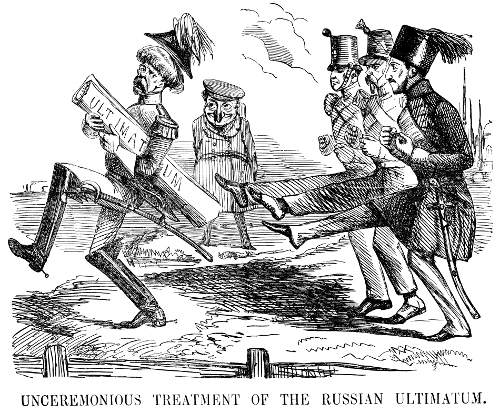

In June 1853, after the collapse of diplomatic relationships with the Ottoman Empire, Russia occupied Moldavia and Wallachia along the Danube, principalities previously under Turkish control. Following this, the Tsar issued a final ultimatum to the Turks. Here the Hussars, representing Turkey, Austria, and France, reject the ultimatum while Britain, in the guise of Punch, looks on contentedly. Both Punch and the Times were part of a strong pro-war lobby in Britain at the time.

In Aesop’s fable, a bear is stung by a bee while sniffing round its hive and attacks the hive in anger; the swarm retaliates and the bear flees in pain. Here the ‘swarm’ is made up of Turkish, Austrian, Prussian, French, and English ‘bees’, protecting the ‘hives’ of Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, against the angry Russian ‘bear’.

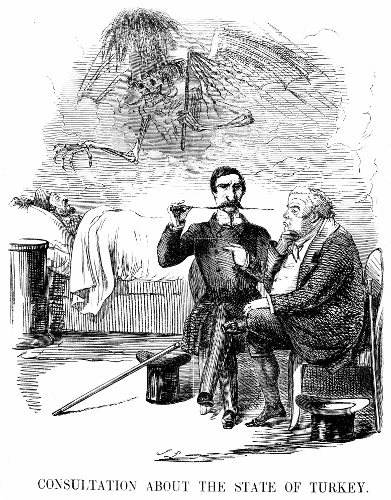

Tsar Nicholas I had once referred to Turkey as ‘a dying man’ in a conversation with Sir Robert Peel and Earl Aberdeen. Nine years later, in 1853, this cartoon portrayed England (John Bull) and France (Napoleon III) beside the Turkish deathbed while the Russian spectre of death hovers overhead.

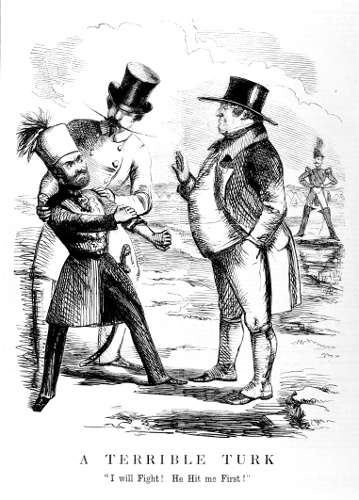

Turkey Provoked

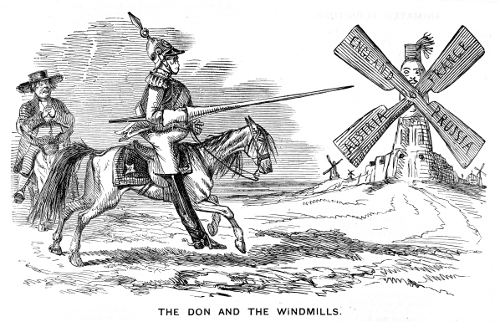

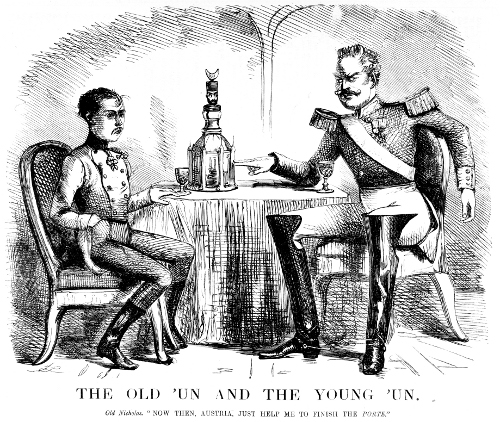

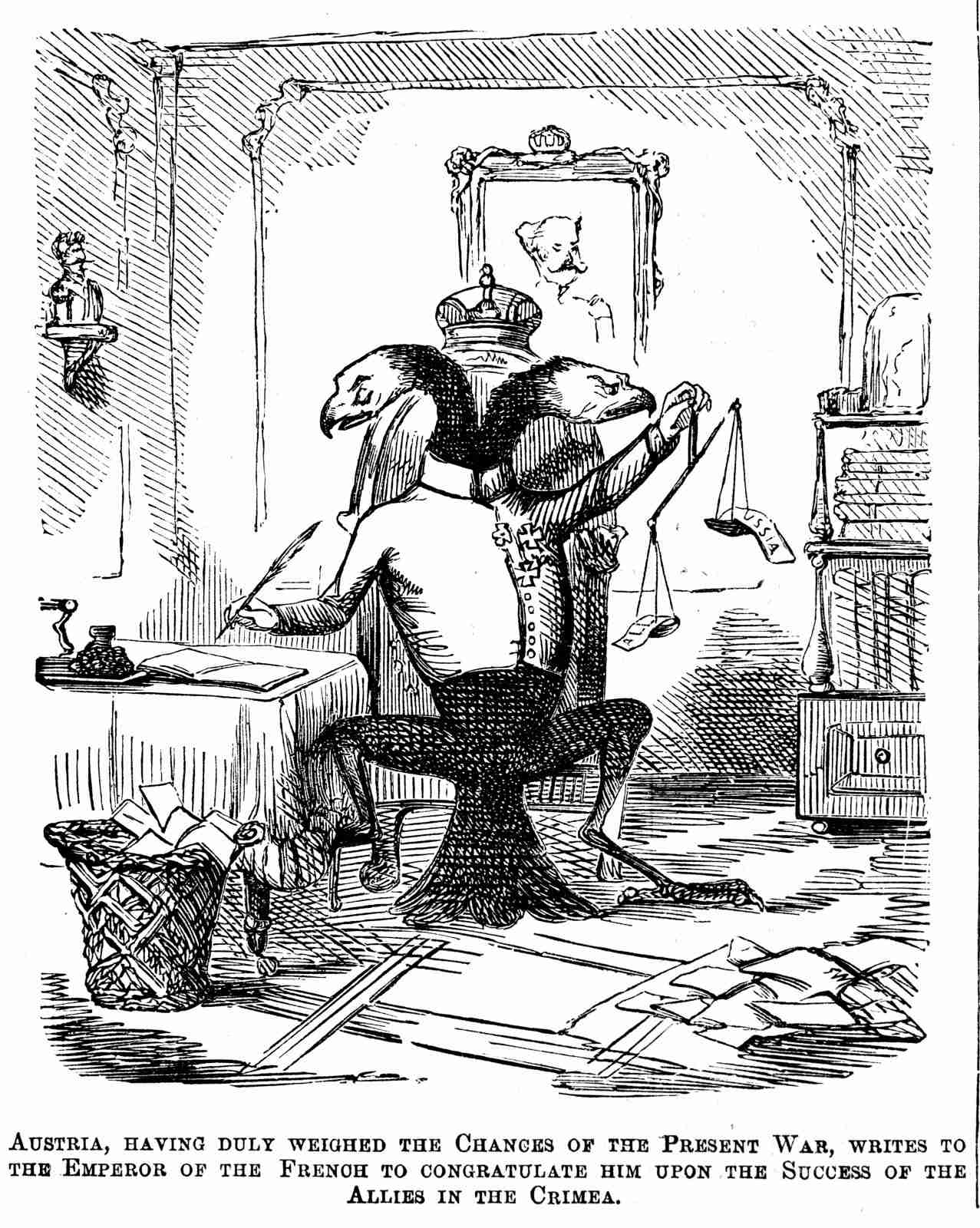

Tsar Nicholas, who had saved the Austrian Empire from destruction by the Hungarians in 1849, now expected Emperor Franz Joseph (more than thirty years his junior) to aid him in the destruction of the Ottoman Empire. However, Franz Joseph was reluctant to antagonise France and England. The sub-caption to the cartoon reads “Old Nicholas – Now then, Austria, help me to finish the Porte”. The Porte was the seat of Ottoman rule in Constantinople.

At first France and Britain tried to avoid war. However, religious leaders in Constantinople declared jihad against Russia, undermining any further attempts at diplomacy. Turkey, fearing an Islamic revolution, was forced to declare war on Russia on 4 October 1853.

War Declared

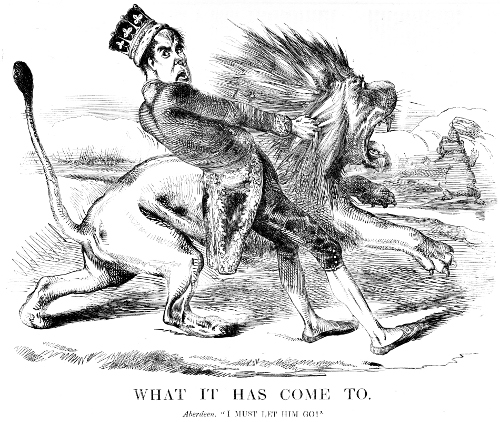

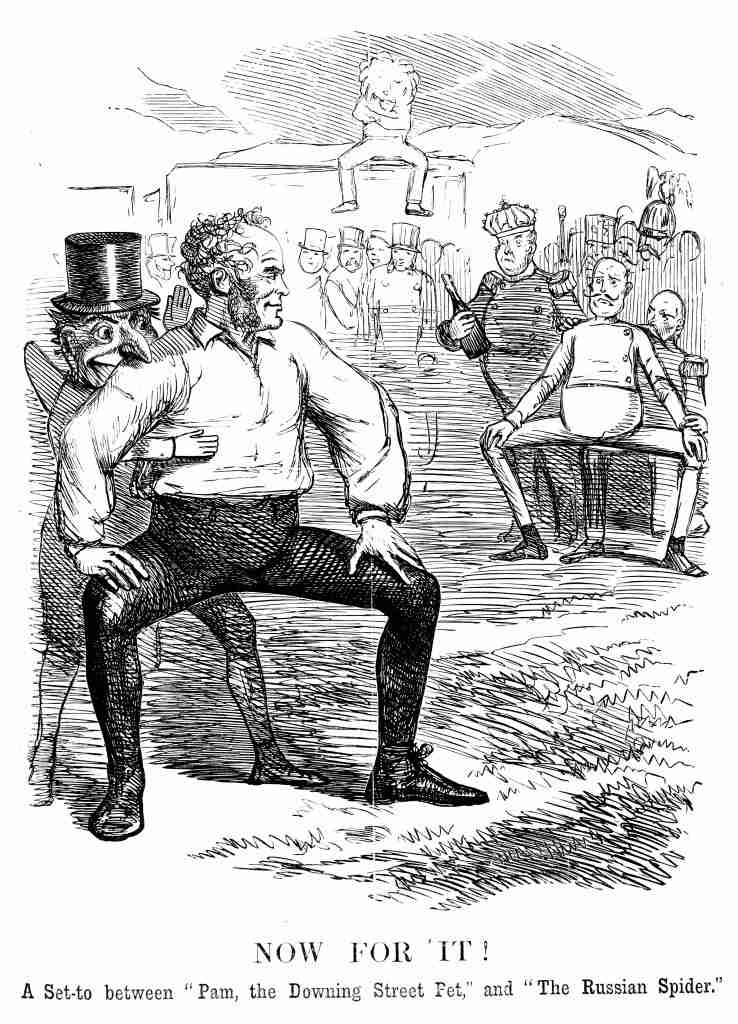

It was England, particularly Lord Palmerston, the Home Secretary, and the British press, who pushed hardest for the Western powers to declare war on Russia. Lord Aberdeen, the Prime Minister, was strongly opposed but eventually conceded to popular opinion and at the end of March, 1854, Britain and France began hostilities with Russia. Prime Minister Aberdeen is depicted vainly holding back the British lion, who strains after a Russian bear, the sub-caption reads “I must let him go!”.

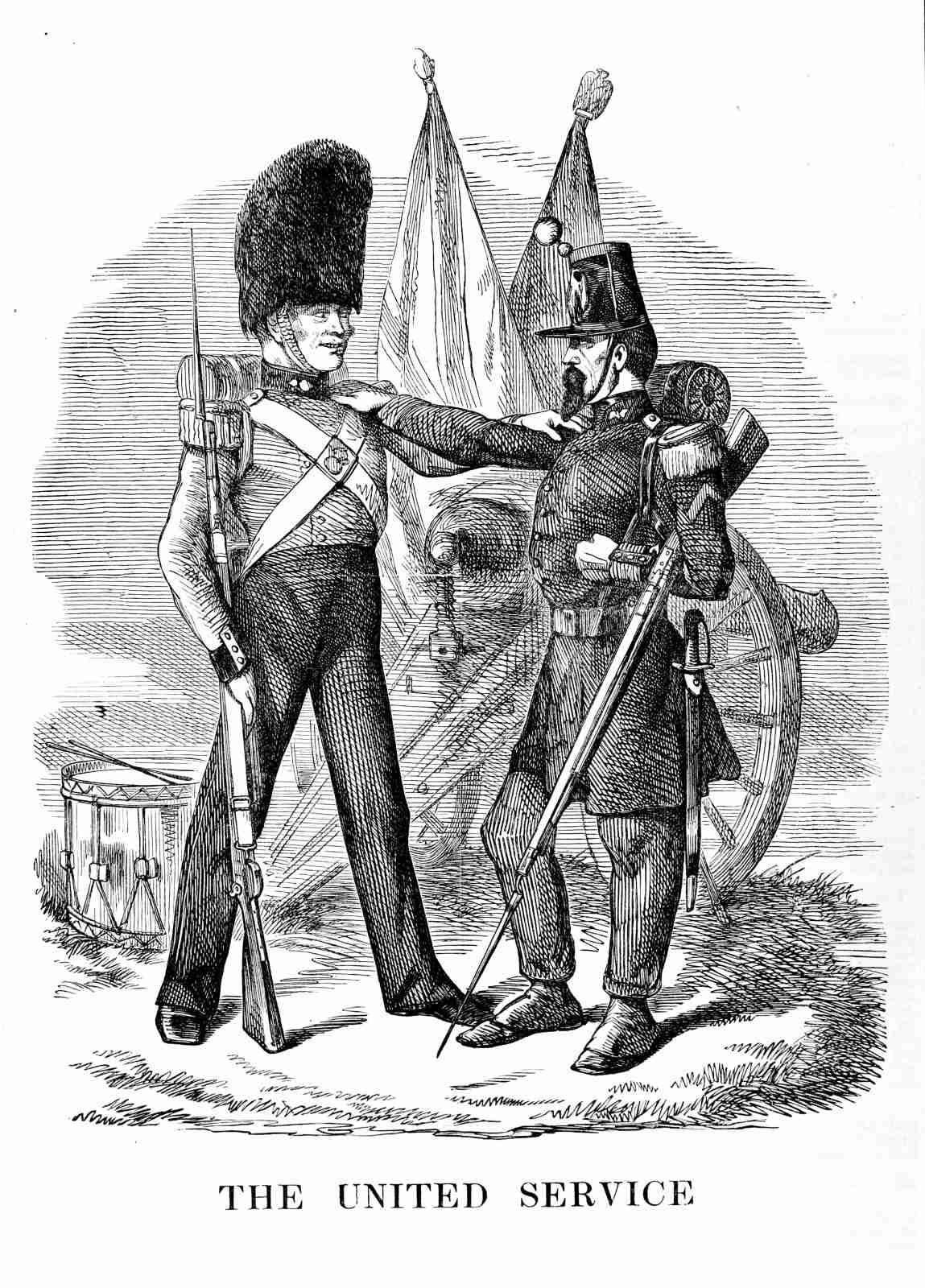

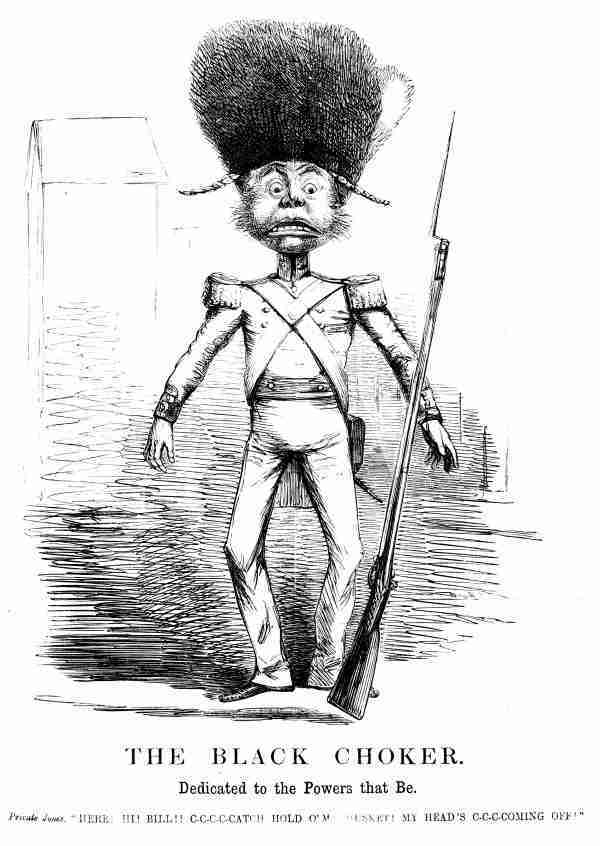

Uniform Discomfort

Shako Badges, Helmet Badges, and other pieces of uniform

A shako was a tall military cap used by both cavalry and infantry troops from the French, British and Russian army in the Crimean War. Helmets were less common but some of the Russian officers did wear a leather bell-shaped helmet surmounted by a tall silver ornament. Brass badges identified the units to which these soldiers belonged.

Russian uniform buttons Left to right:

- 23rd Infantry (EUR128b);

- Unknown regiment (EUR128c);

- Sapper (EUR128d);

- 19th Infantry (EUR128e)

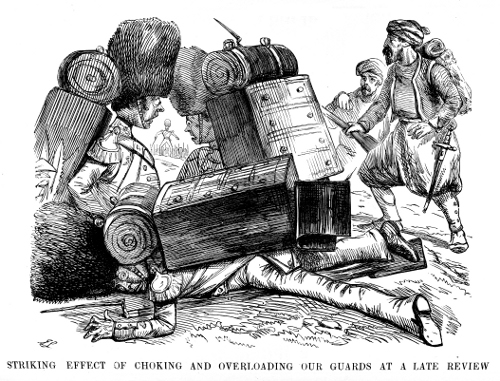

General Lord Raglan, a British hero of the Napoleonic Wars, insisted that his troops went into battle in smart, but impractical, parade uniform. It took a public outcry to change this. ‘A suit on his back and a change in his pack is all that the men require but still he is loaded like a donkey … The reasoning of 40 years experience would not move the military authorities to let the soldier go into the field until he was half strangled and unable to move under his load…’ (Lieutenant Colonel George Bell).

Badges of the British Royal Fusiliers. ‘Honi soit qui mal y pense’ is the motto of the English chivalric Order of the Garter. Its literal translation is ‘Evil be to him who evil thinks’.

Most British troops all wore an uncomfortable tall Shako, thought to have been designed by Prince Albert and made of pressed and steamed black felt, with a lacquered leather top and peak. It was known as the ‘Albert’. The regiments represented above all lost men in the failed assault of the Redan bastion on 8th September, 1855

Top, left to right:

- 38th (1st Staffordshire) Regiment of Foot shako badge. EUR112

- 62nd (Wiltshire) Regiment of Foot shako badge. EUR113

- 88th Regiment of Foot (Connaught Rangers)shako badge. EUR114

Bottom, left to right:

- 55th (Westmorland) Regiment of Foot. EUR123

- Regimental Band shako badge, unknown regiment. EUR115

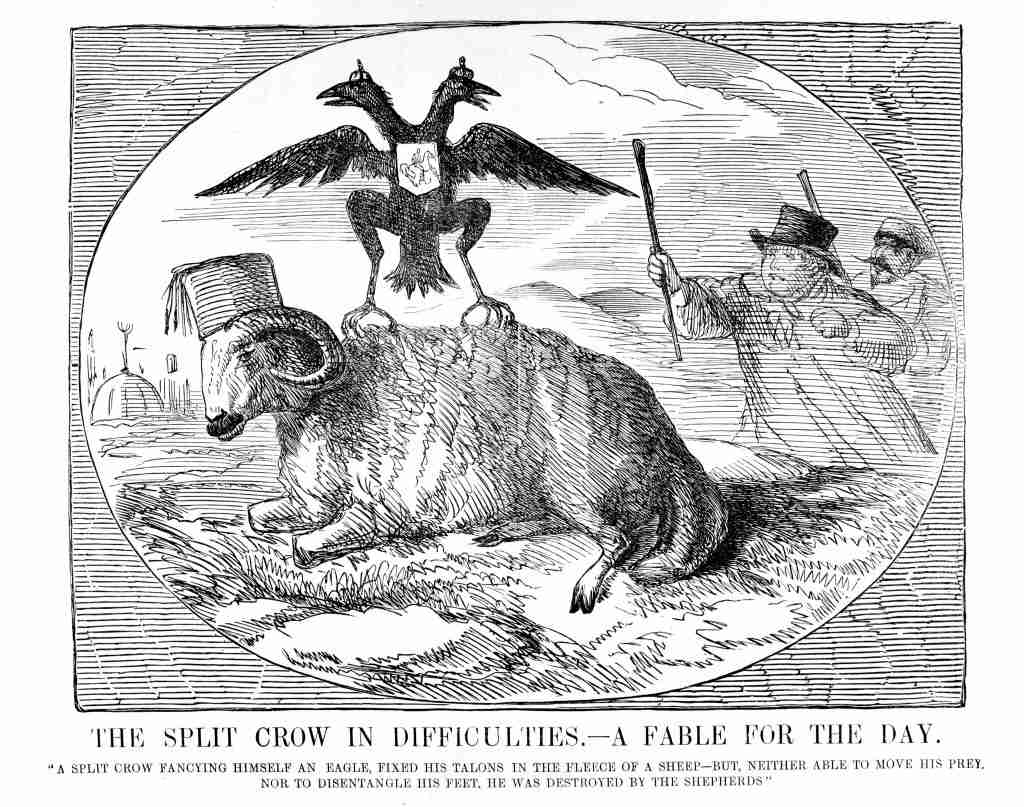

The symbolism is obvious; Turkey is the peaceful sheep and Russia the overambitious carrion bird, while John Bull (England) and his friend (France) play the parts of the shepherds.

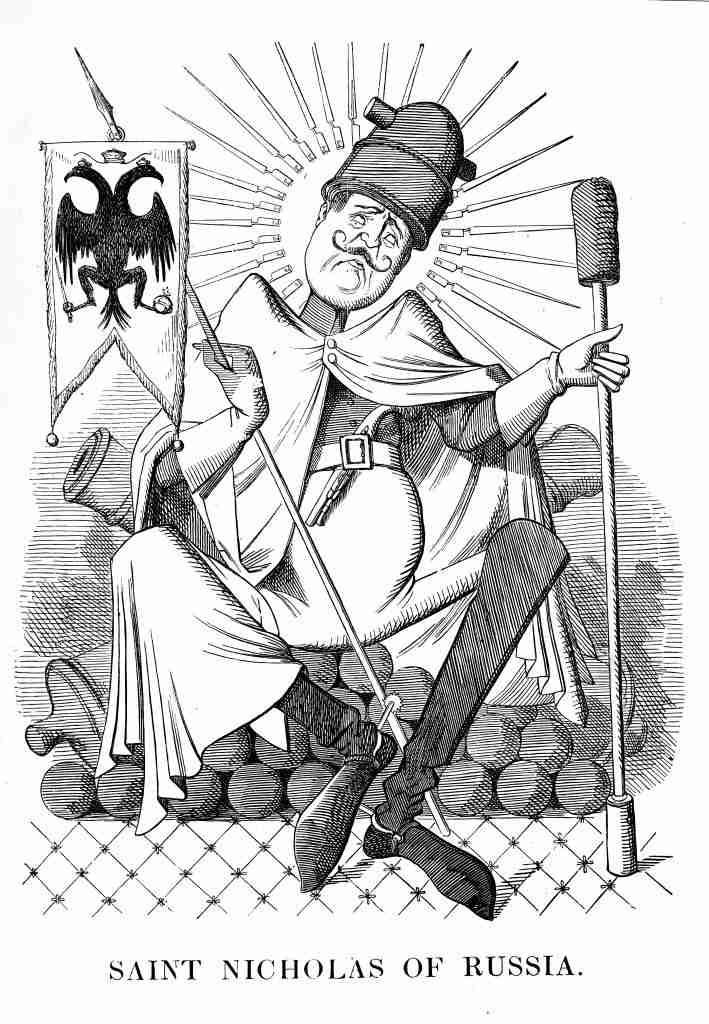

In this parody of an Orthodox Christian icon, the Tsar is seated on cannon balls, with a ramrod as a crozier, a mortar as a mitre, and a halo of bayonets.

The Tsar’s aggression against the Ottoman Empire was motivated by his desire to defend the Greek and Russian Orthodox faith against Islam. He assumed Christian nations of Europe would join him in this ‘sacred duty’. However, general opinion in Catholic France and Protestant Britain was that Ottoman rule was more tolerant of their faiths than the feared despotic rule of the Orthodox Church.

Montagne Russe was a name given by the French to the earliest rollercoasters, brought to Paris in 1816, inspired by the Russian custom of building perilous snow slopes for racing sledges. Here the apparently nonchalant Tsar rides the sledge of despotism off a cliff edge.

Bombardment

This conical wooden fuse was designed for use in a mortar shell considerably larger than the shell fragment below. Packed with compressed black powder and turned with regular gradations, representing roughly a seconds burn time, and grouped into sections of five seconds, the fuse would be trimmed to burn for the appropriate time. The narrow end was wedged into the opening of a spherical iron explosive shell and fired from the mortar fuse first; the fuse would ignite with the propelling charge and the shell would explode at the appropriate moment in its trajectory.

Collected from Sevastopol by Dr T. E. Hale, and donated by his niece Mrs. Dugan in 1927.

During the eleven and a half month long siege of Sevastopol a combined estimate of five million shells, mortars and other explosive artillery rounds were fired. This was the first war in which such weapons were used on an industrial scale, a precursor of the World Wars. Shells fired from cannon like howitzers with a low angle trajectory used a wooden bottom called a sabot, ensuring the fuse was presented to the mouth of the gun, but mortars fired at high angle parabolic trajectories did not.

Collected from Sevastopol and donated by Arthur Warne Weston, 1869

Round shot were solid cast-iron cannon balls. These particular round shot weigh about 3 lb (1.36 kg) and were probably fired from a lightweight infantry support gun with a bronze barrel, known as a grasshopper. The range of cannons and ammunition employed in the Crimean War was greater than ever before. Cannons firing 12 lb (5.44 kg) and 18 lb (8.16kg) were common, but the largest bore guns used in the Crimean War were 13 inch (33 cm) mortars.

Collected from Sevastopol and donated by Arthur Warne Weston, 1869.

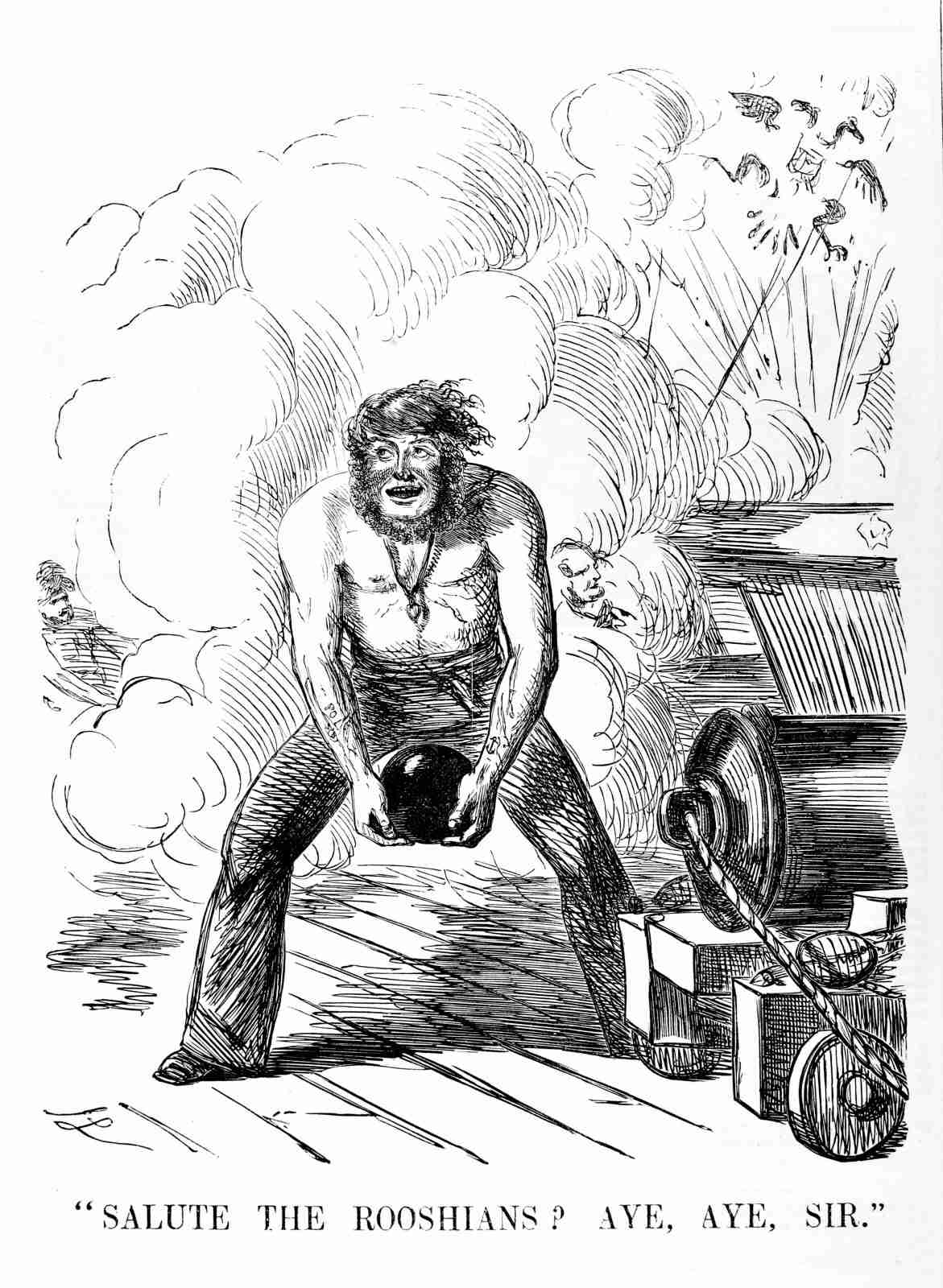

The Conflict Begins

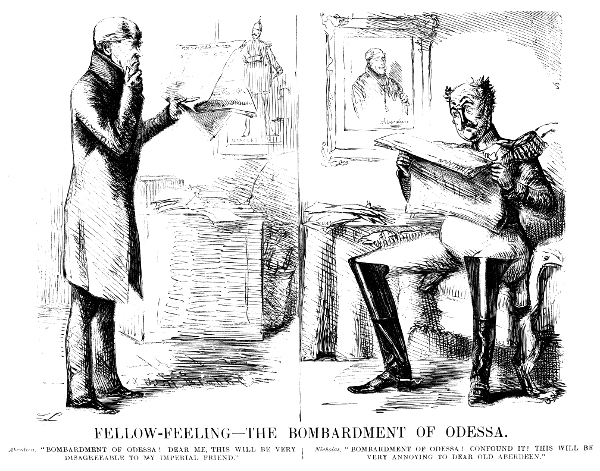

The Western naval fleets bombarded the port of Odessa on 22 April and 12 May 1854, the first direct attack on Russian soil by the allies. The hope of both Aberdeen (the British Prime Minister) and Tsar Nicholas that a Western conflict with Russia could still be averted was now dashed. The sub-caption of the cartoon above reads: ‘Aberdeen “Bombardment of Odessa! Dear me, this will be very disagreeable to my imperial friend” Nicholas “Bombardment of Odessa! Confound it! This will be very annoying to dear old Aberdeen”’.

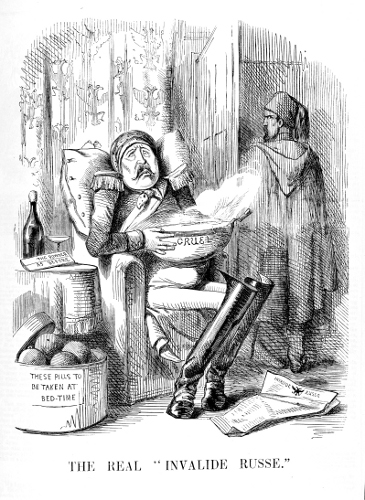

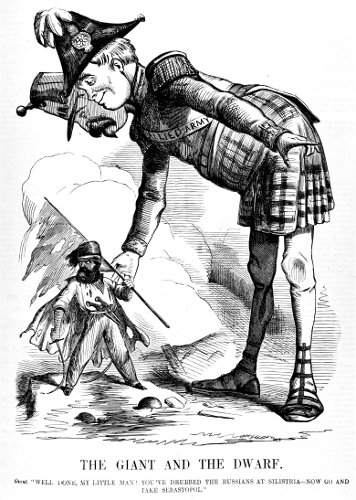

Throughout May and June the Russians laid siege to the Ottoman fortress of Silistra. The Turks mounted a fierce defence and eventually the Russians, fearing the imminent arrival of French and British troops, were forced to retreat across the Danube. This was reported in the Russian military newspaper, Invalide Russe, as a tactical withdrawal and a Russian victory.

A Russian short defensive sword known as a “sidearm” was usually issued to soldiers manning artillery. The single edge curved steel blade is edge formed with prominent saw teeth along the back.

Collected from Sevastopol by J.D. Mant and donated by H. Mant, 1856.

EW015

This traditional sword of the Cossacks, the Shashka, was adopted as the sword of the Russian cavalry.

Collected from the Battle of Inkerman and donated by Major Christopher Brice Wilkinson, 1882.

EW014

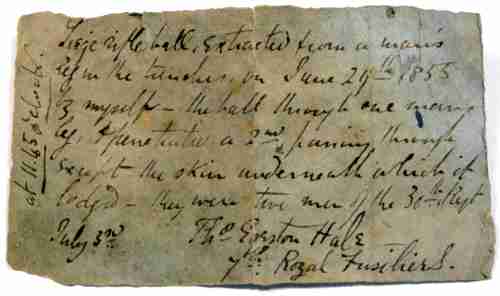

Dr T.E. Hale’s Crimean Relics

Thomas Egerton Hale (1832-1909) was commissioned as Assistant Surgeon with the 7th Regiment of Foot (Royal Fusiliers) in 1854 and saw active service with them in the Crimea, and later during the Indian Mutiny. He was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery at Sevastopol. The citation for this award was published in the London Gazette on 5th May 1857as follows: –

1. For remaining with an officer who was dangerously wounded (Capt. H.M. Jones, 7th Regt.) in the fifth parallel on 8 Sept. 1855, when all the men in the immediate neighbourhood retreated, excepting Lieut W. Hope and Dr Hale; and for endeavouring to rally the men, in conjunction with Lieut. W. Hope, 7th Regt. The Royal Fusiliers.

2. For having on 8 Sept. 1855, after the regiment had retired into the trenches, cleared the most advanced sap of the wounded, and carried into the sap, under heavy fire, several wounded men from the open ground, being assisted by Sergt. Charles Fisher, 7th Regt. The Royal Fusiliers.

Dr Hale kept a few souvenirs from his medical work:

Candlestick used when removing a bullet from a man’s leg (EUR099)

Tige (systeme a tigé) rifle bullet extracted from a man’s leg in the trenches of Sevastopol on June 24th 1855 (at 11.45), alongside a similar bullet with the tip deformed from impact. Removed from a man’s arm in April 1855 by Dr Hale. The two projections either side of the bullets were designed to engage the rifling of the barrel. (EUR101 EUR101A)

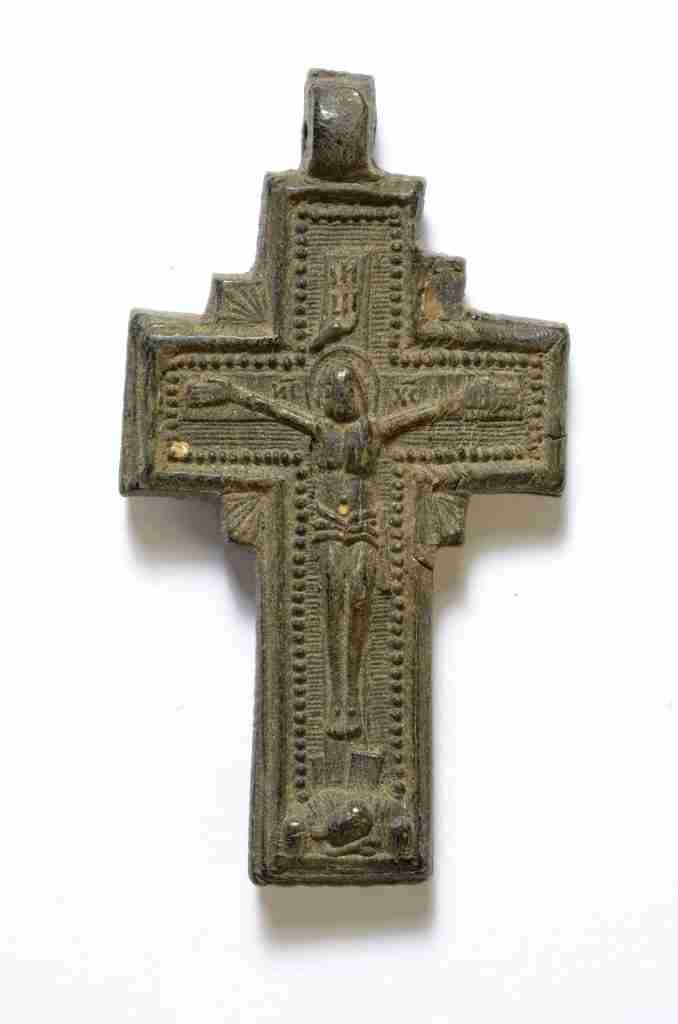

Crucifixes and rosaries: Orthodox Christianity was very important to most of the Russian troops, and almost every Russian soldier would have worn some type of crucifix.

Above: Wooden rosary with cross attached (EUR106A) and assorted Crucifixes (EUR107+a-g)

Below: Baltic amber rosary with crucifix and St. Benedict talisman (EUR106)

Taking trophies from dead bodies of Russian soldiers was popular amongst the British troops. For example, in a letter to his mother Hugh Drummond of the Scots Guards wrote: ‘I have got a beautiful trophy for you from the Alma, just one to suit you, a large silver Greek cross with engravings on it – (?)our saviour and some Russian words; it came off a Russian Colonel’s neck we killed, and, poor fellow, it was next to his skin.’

On to the Crimea!

The Invalide Russe was the Russian army newspaper in which propagandist accounts of military engagements were published. Here the Tsar is treated with pills in the form of bombshells by a Turkish doctor, following Russia’s withdrawal from the Danubian Principalities.

Once the Russians had withdrawn from the Danubian Principalities, following their failure at Silistria, the war could have ended, with the Turks establishing a peace-keeping presence. However, Britain and France had mobilised such a substantial force that they were determined to take further action against the Russians; they chose the destruction of the fortified port of Sevastopol and the Black Sea Fleet as their next objective.The sub-caption reads ‘Giant “Well done, my little man! You’ve drubbed the Russians at Silistria – now go and take Sebastopol”’.

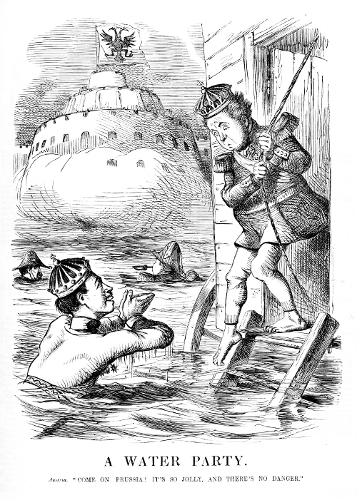

Austria swims behind France and Britain in order to attack Sevastopol, while Prussia has to be coaxed out of the bathing machine; it followed Austria’s lead in foreign affairs and Austria took no active role in the Crimean offensive.

Following Russia’s withdrawal from the Danubian Principalities, Austria held a policy of armed neutrality in favour of the allies for the rest of the war.

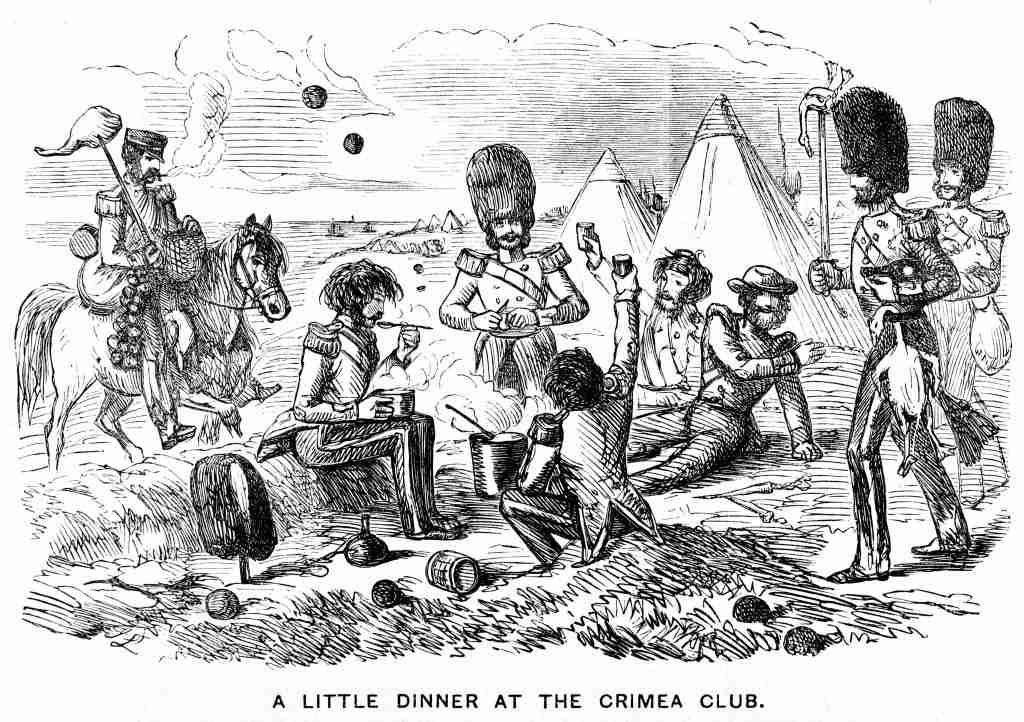

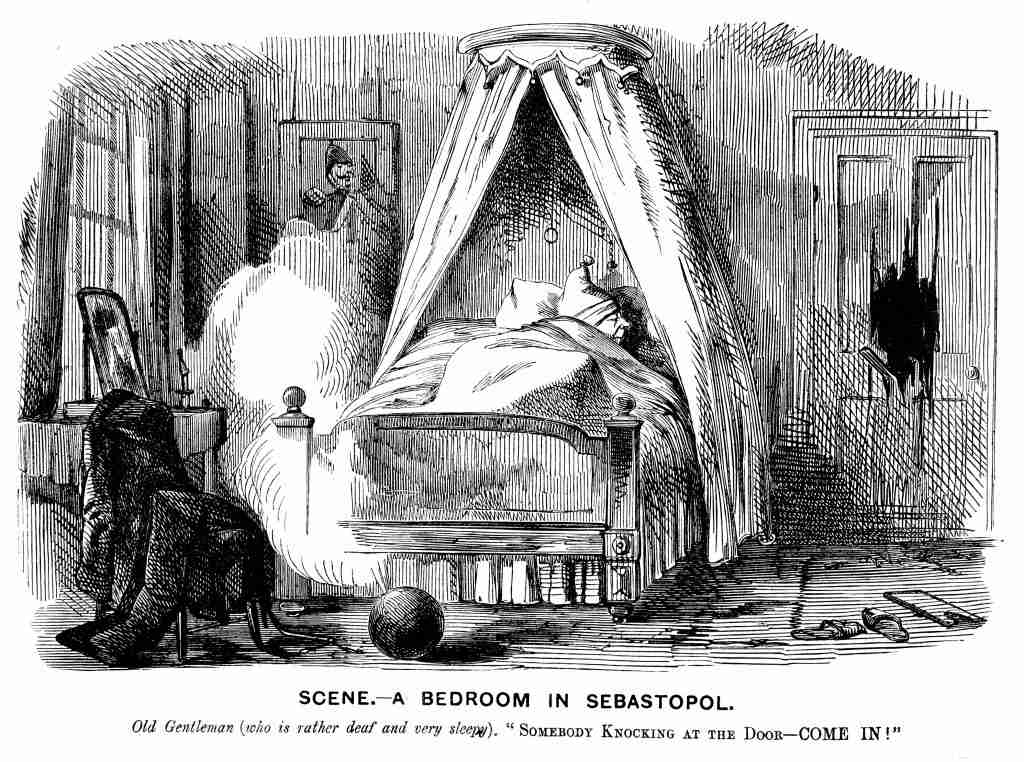

Bombardment at Sevastopol

During the year long Siege of Sevastopol, 120km of trenches were dug, with 150 million bullets and 5 million shells fired. However, life had to continue as normal for the troops on both sides, while cannonballs and mortar shells fell around them.

Russian tobacco pipe and rough carved spoon, inscribed ‘Tchernaya’

Collected by Dr. T. E. Hale, and donated by his niece Mrs. Dugan in 1927

The Battle of Tchernaya (or Chernaia) (August 16th 1855) was a last desperate attempt by the Russians, on the insistence of Tsar Alexander II and against the advice of his senior officers in the field, to break the Siege of Sevastopol. The Russian attack was a terrible failure, despite 47,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 270 field guns being deployed against just 18,000 French and 9,000 Sardinians; the fortified position and better training and equipment of the allies gave them too great an advantage. The British troops were joined by war tourists, medics, and even army chaplains, to gather souvenirs from the bodies of the Russian dead and wounded.

Starvation Rations

A piece of Russian bread; the fact that it has survived nearly 160 years without rotting is testament to its poor quality, it contains grit and a lot of chaff.

In his excellent book Crimea Orlando Figes writes of “rations of dry bread that were so devoid of nutrition that not even rats and dogs would eat them … Grigory Zubianka, a foot soldier in the 8th Hussars Squadron, wrote to his wife Maria on 24th March [1854]: …’we are made to spend all day and night in hunger and the cold, because they give us nothing to eat and we have to live as best we can by fending for ourselves, so help us God.’”

Collected from Sevastopol by Dr T. E. Hale, and donated by his niece Mrs. Dugan in 1927.

EUR102

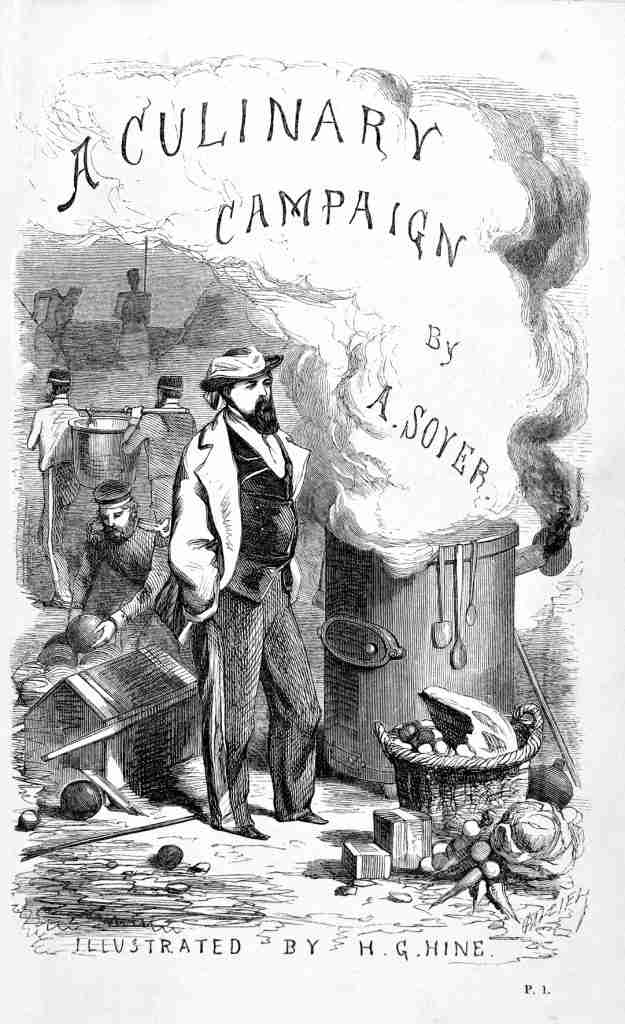

Alexis Soyer, the French chef at the Reform Club in London, travelled to the Crimea in the spring of 1855 on a mission to improve the diet of the British soldiers, and chronicled his experiences in this book, published 1857. Soyer’s major contribution was the introduction of collective provisioning, distributed through mobile field canteens, a system used by the French since the 18th Century.

To read more about Soyer’s Culinary Campaign visit our page here.

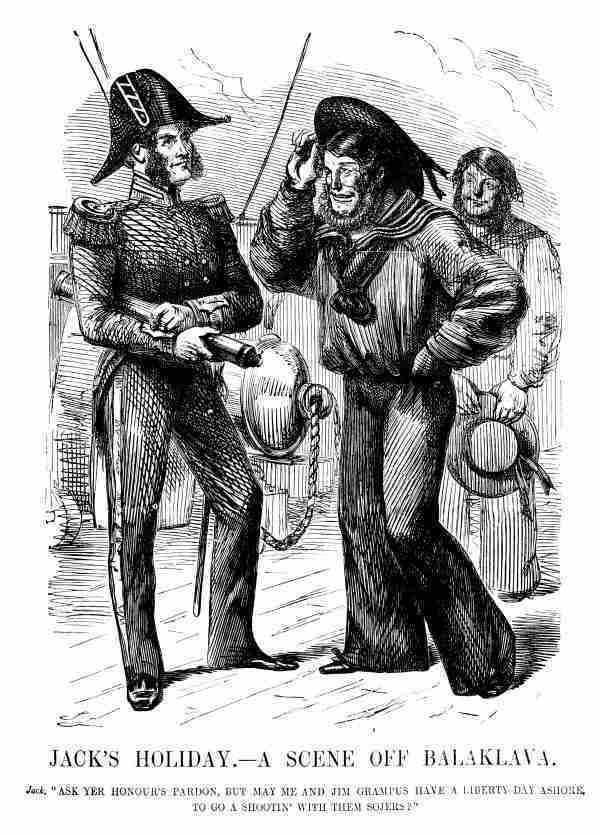

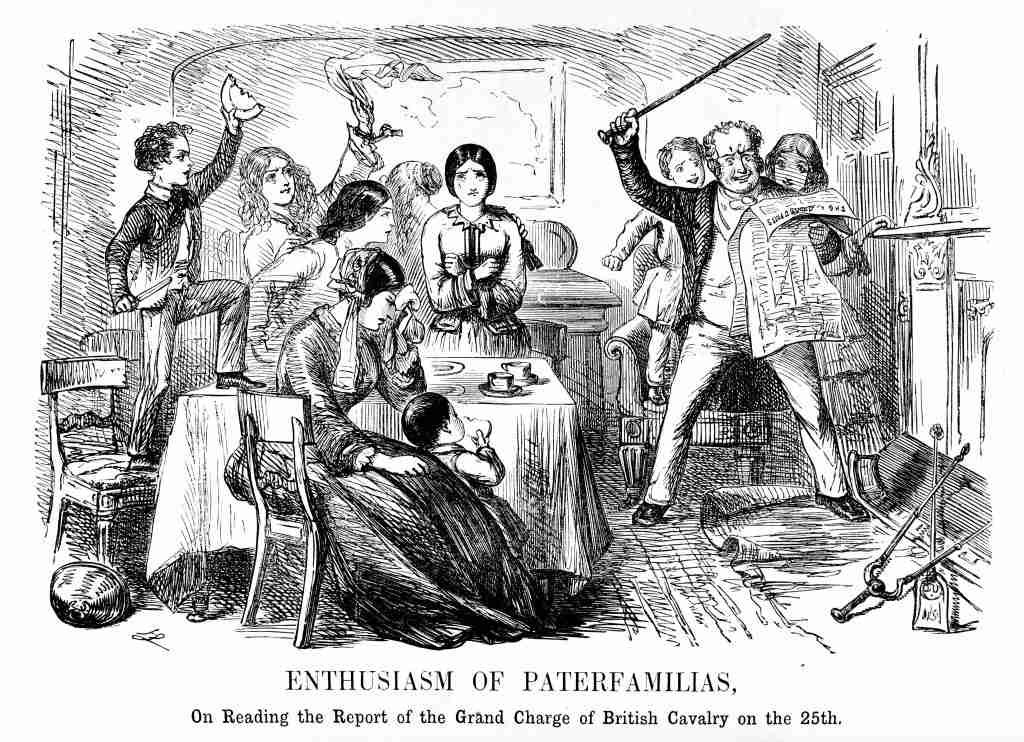

Battle of Balaclava

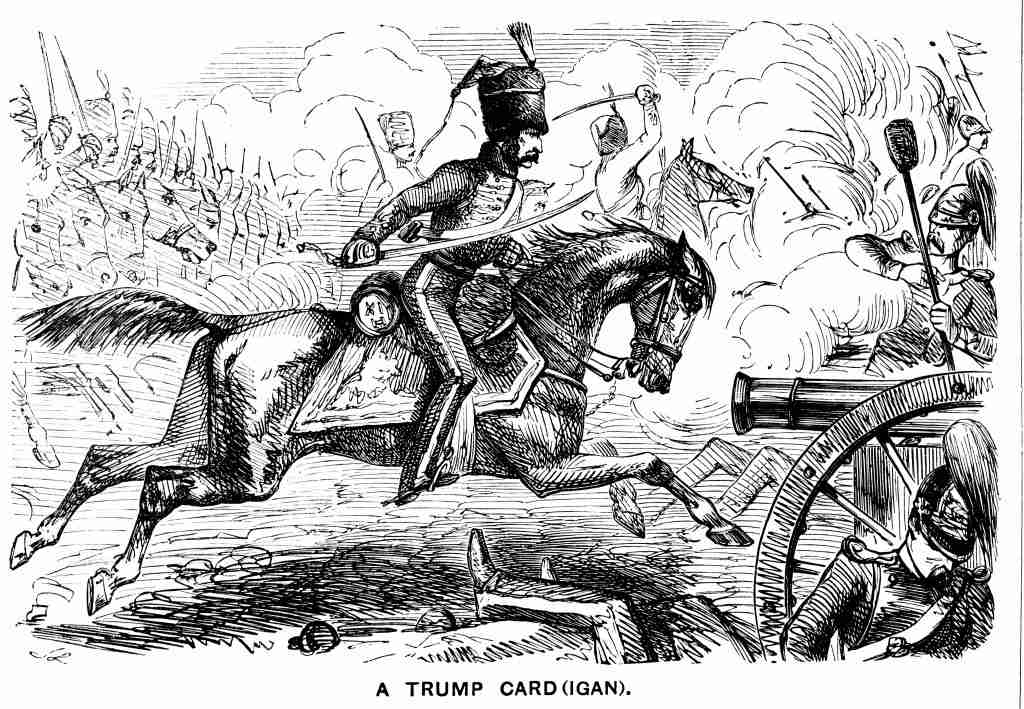

The charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava was a military bungle, largely the result of poor communication between General Lord Raglan, the Commander of the Cavalry Lord Lucan, and Commander of the Light Brigade Lord Cardigan (Lucan’s brother-in-law and bitter rival). The Light Brigade were already frustrated by being given no chance to prove their valour in the campaign, and an ambiguous order caused them to charge willingly into heavy fire on three sides.

This lance was the weapon most commonly used by the Imperial Russian army’s Cossack irregular cavalry. The Cossacks, a mix of ethnic Tartars and the descendants of escapee serfs from all over the Slavic regions, lived in semi-independent self-governing military communities, but had a strong sense of loyalty to the Tsarist government and were an important supplement to their armies. The iron socket of the spearhead is bound to the shaft with leather thongs;it is broad to allow easy withdrawal from an impaled body and to prevent the pierced enemy sliding up the lance.

Collected from Sevastopol. Donated by Dr Hamilton of 11 Great Bedford Street, 1876.

EUR565

The port of Balaclava was the main base of supplies for the British during the Siege of Sevastopol, which lay 10 miles overland on the far side of the peninsula. The Battle of Balaclava, on the 25 October 1854, was a successful assault on the British position by Russian forces, weakening the British supply lines and delaying a decisive breaking of the siege for many months.

Lord Cardigan led the disastrous charge down the valley with 661 men, of whom 113 were killed, 134 wounded, and 45 taken prisoner, with 362 horses lost. The war correspondent William Howard Russell gave a now famous account of the event in the Times (the same account read here by ‘paterfamilias’ ):

“If the exhibition of the most brilliant valour, of the excess of courage, and of a daring which would have reflected luster on the best days of chivalry can afford full consolation for the disaster of today, we can have no reason to regret the melancholy loss which we sustained in a contest with a savage and barbarian enemy”.

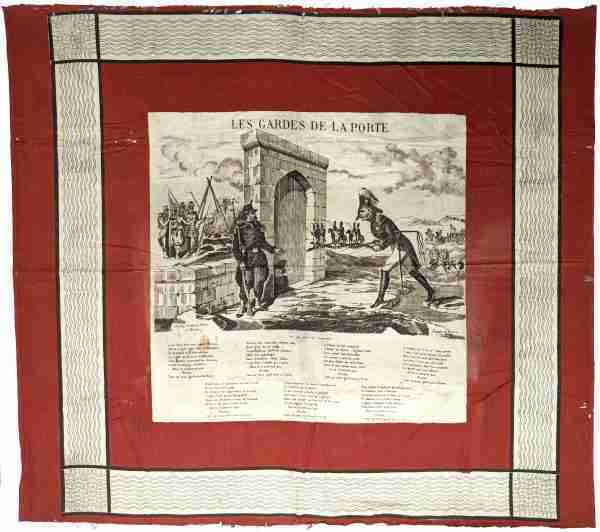

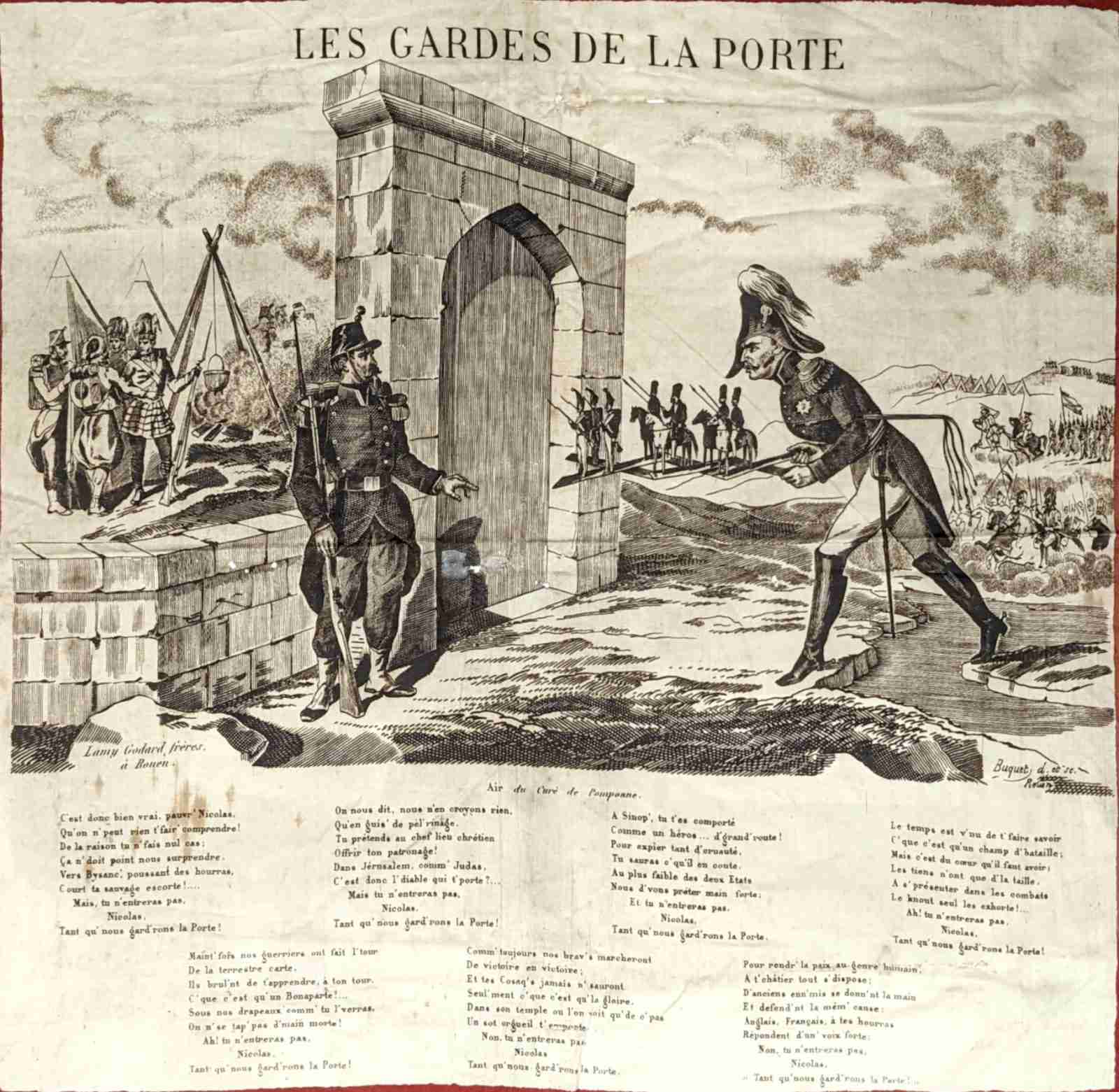

French “Rouen Handkerchiefs”

The printers Lamy Godard Brothers of Rouen worked with N.A. Buquet, illustrator and engraver, to produce commemorative printed cotton handkerchiefs. The particular designs, seen in this case and its counterpart, were produced in 1854.

The handkerchiefs were aimed at a popular audience and could either be worn round the neck or displayed by pinning them to a wall. 32 different designs relating to the Crimean War were produced and there is good evidence that many of these were shipped out to the Crimea and sold by peddlers around the various military camps, which is probably where Dr Hale purchased his.

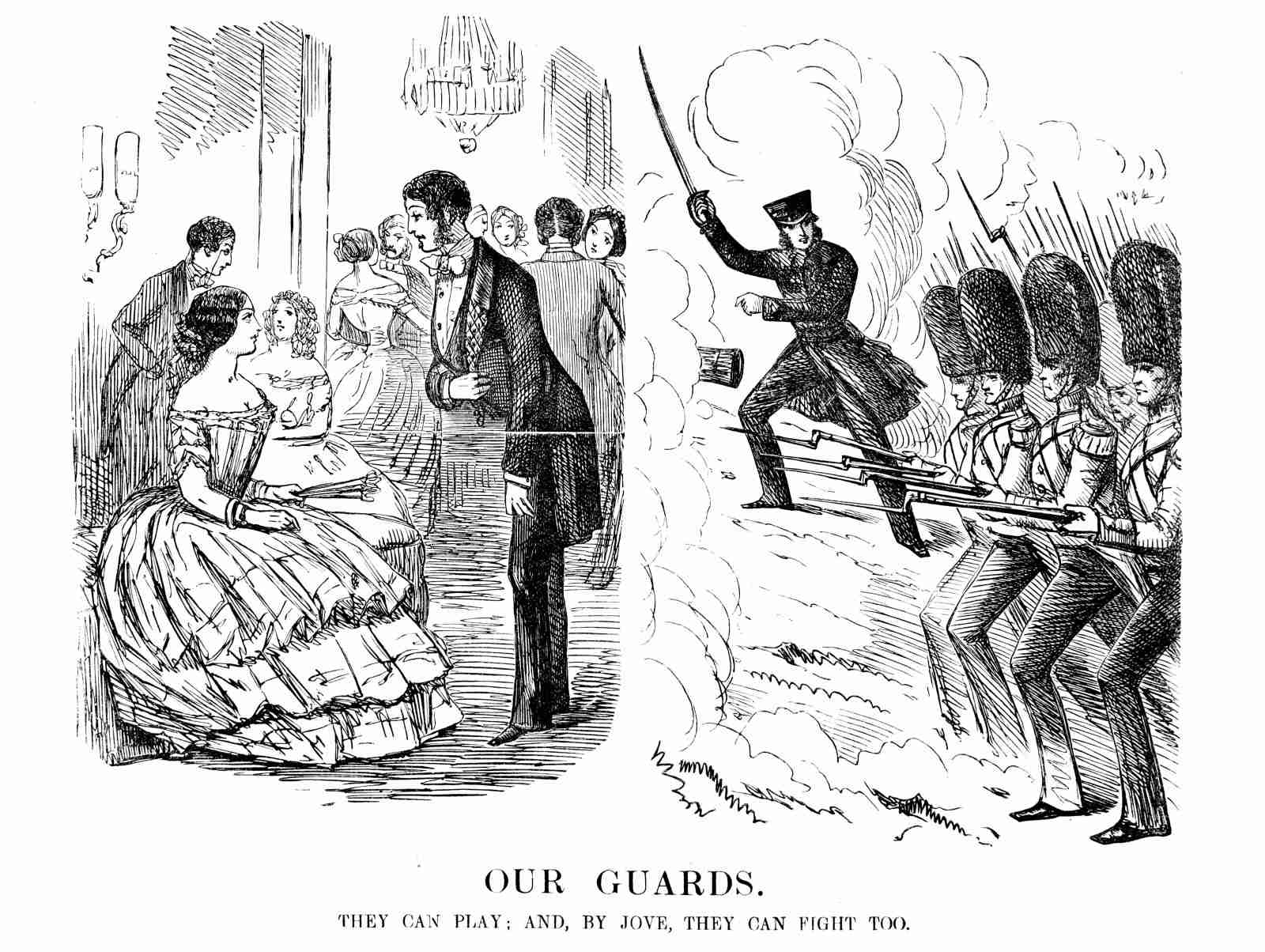

Guards of the Gate

The original sketch for this print, from Buquet’s studio, is held by the Musée des Traditions et Arts Normands near Rouen.

Collected by Dr T. E. Hale, and donated by his niece Mrs Dugan in 1927.

EUR132

The poem can be translated roughly as follows:

Then this is true, poor Nicolas,

That no one can make you understand anything!

Of reason, you don’t attach any importance.

This should not surprise us.

Toward Byzantium, cheering,

heads your savage escort!…

But you, will not enter,

Nicolas,

As long as we will guard The Gate!

One tells us, but we don’t believe a word,

That in the guise of a pilgrimage,

To the administrative centre of Christianity

You aspire to offer your patronage!

In Jerusalem, like Judas.

So are you inhabited by the Devil?

But you, will not enter,

Nicolas,

As long as we will guard The Gate!

At Sinop you behaved

Like a hero…of the highway!

To atone for so much cruelty,

You will learn the price.

To the weakest of the two states

We must lend a hand:

And you, will not enter,

Nicolas,

As long as we will guard The Gate!

The time has come to let you know

What a battlefield is.

But one must have some heart,

Your army has only got size.

When they show up during fights

Only the Knout* gives them courage!

Ah! You will not enter,

Nicolas,

As long as we will guard The Gate!

So many times our soldiers went round

The terrestrial map.

They can’t wait to teach you, in your turn,

What a Bonaparte is!…

Under our flags, as you’ll see

We don’t pull the punches!

Ah! You will not enter,

Nicolas,

As long as we will guard The Gate!

As always our braves will march

From victory to victory,

And your Cossacks will never know

What glory only is.

In your temple, where one sees right now

That a foolish pride prevails over you

No, you will not enter,

Nicolas,

As long as we will guard The Gate!

In order to bring back the peace to mankind,

Chastising you and everything becomes clear:

Old enemies holding hands together

And defending a common cause.

British, French, to your cheers

All answer with a strong voice:

No, you will not enter,

Nicolas,

As long as we will guard The Gate!

[* a Russian whip used for punishing serfs]

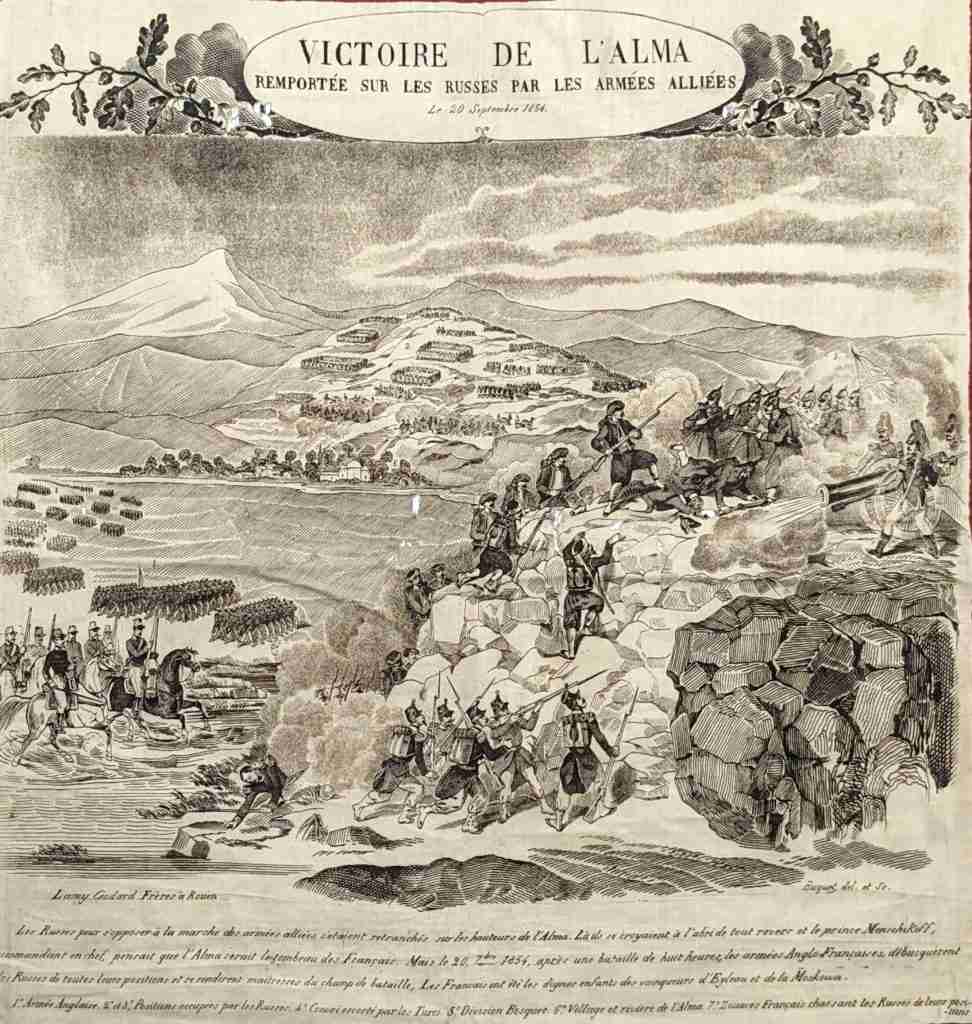

Victory of Alma

Won over the Russians by the allied armies

On the 20th of September 1854

Collected by Dr T. E. Hale, and donated by his niece Mrs Dugan in 1927.

EUR132a

The account can be translated roughly as follows:

The Russians, in order to prevent the march of the allied armies, were hiding at the heights of Alma. There, they believed to be safe from any attack and Prince Menschikoff, chief commander, thought that the Alma would become the grave of the French. But on September the 7th of 1854, after an eight hour long battle, the Anglo-French armies flushed out the Russians from their positions and became the masters of the battlefield. The French were the worthy children of the winners of Eyleau and Moskowa*

1. British army, 2. and 3. Positions occupied by the Russians, 4. Convoy escorted by the Turks, 5. Bosquet Division, 6. Village and River of Alma, 7. French Zouaves hunting the Russians out of their positions

(*two battles between France and Russia in 1807 and 1812 respectively)

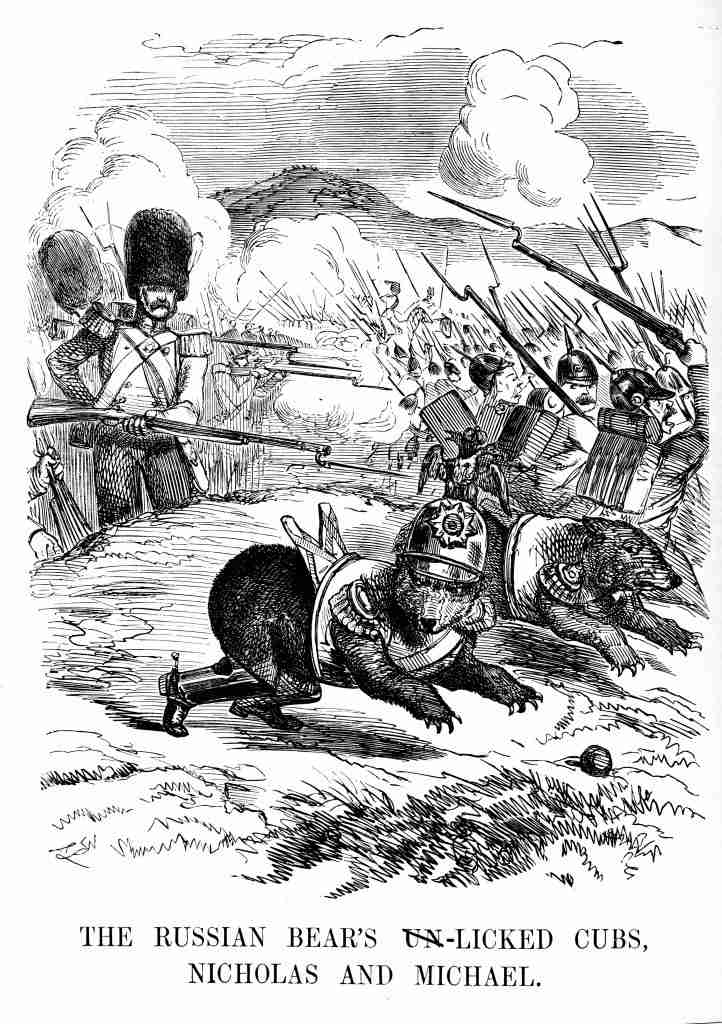

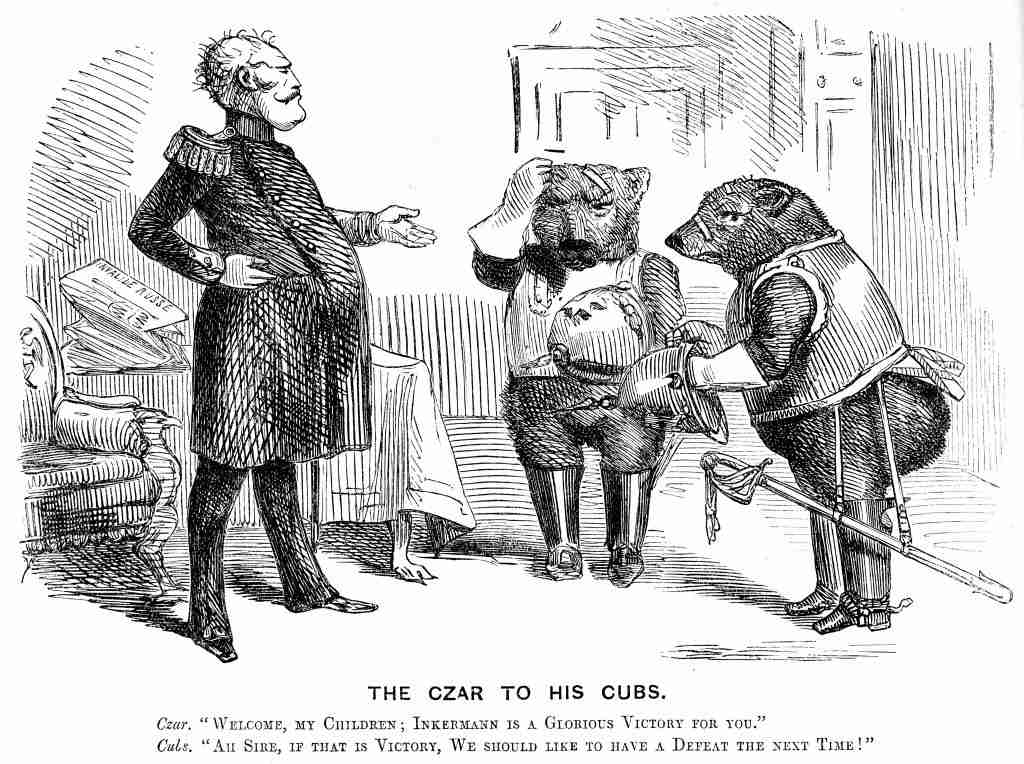

Battle of Inkerman

The Tsar ordered an assault on the allied forces on 5 November 1854, in order to break the siege of Sevastopol before the arrival of French and British reinforcements. He sent his sons to Inkerman Heights, to the east of the town, to encourage the Russian troops. Foggy conditions and the mountainous terrain caused chaos on both sides and the Russians suffered a serious defeat; in just four hours 12,000 Russian, 2,610 British, and 1,726 French soldiers died in combat.

Russian Bugle

Inscribed ‘Inkerman Nov. 1854’, this bugle was either dropped or fell with its owner at a battle that claimed over 12,000 Russian lives in just four hours. Its collector, Christopher Brice Wilkinson, purchased a commission as Ensign of the 68th Regiment of Foot (Durham Light Infantry) in October 11th 1853, was promoted to Lieutenant a month before the Battle of Alma (September 1854), and made Captain in January 1855. He fought in every battle of the Crimean War and was made Major in 1858. He donated this bugle and other items from the Crimean War in 1882, by which point he was Chief of Police in Bath.

EUR098

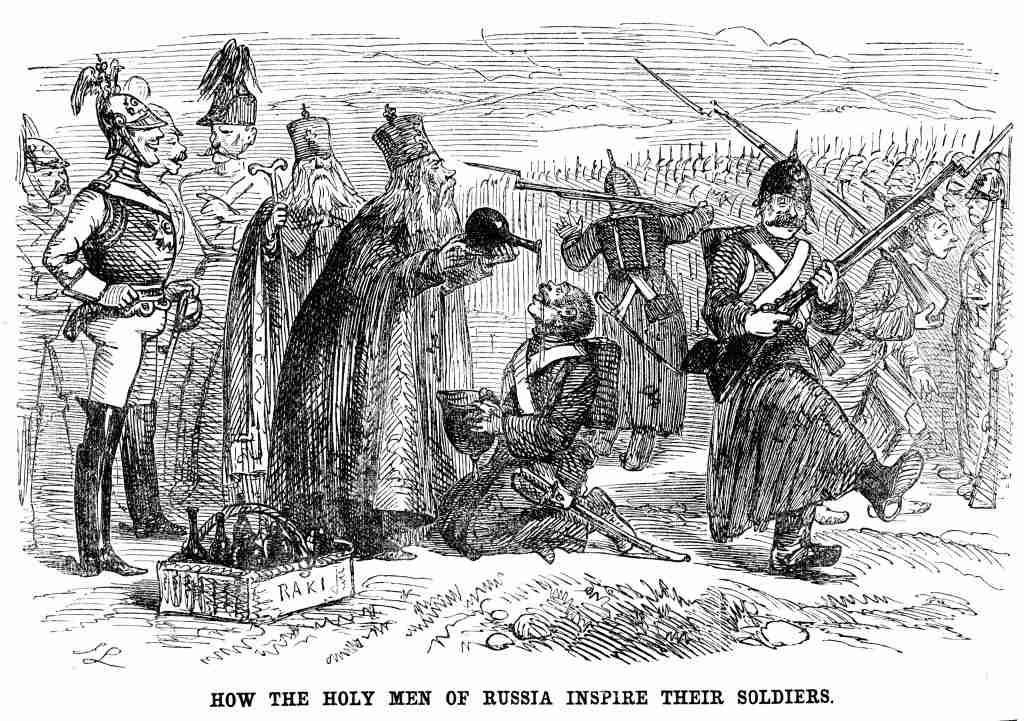

Following the Battle of Inkerman, the Russian troops were criticised for their barbarity, including allegations of the drunken butchering of wounded allied soldiers.

Here truth is mixed with fantasy and propaganda. The night before the battle, the Orthodox priests had declared that the French and English were fighting for the devil, a claim inflamed by their genuine grievance regarding the desecration of an important Russian Orthodox Church that had been pillaged and incorporated into the French siege works.

A Russian Infantry side drum, Similar drums were used by all sides to give battle signals as part of a fife and drum corps, playing short pieces to communicate to field units. This artefact has been partially reconstructed to demonstrate the appearance of the undamaged original.

Collected at Sevastopol.

Donated by Dr Hamilton of 11 Great Bedford Street, 1876

EUR581

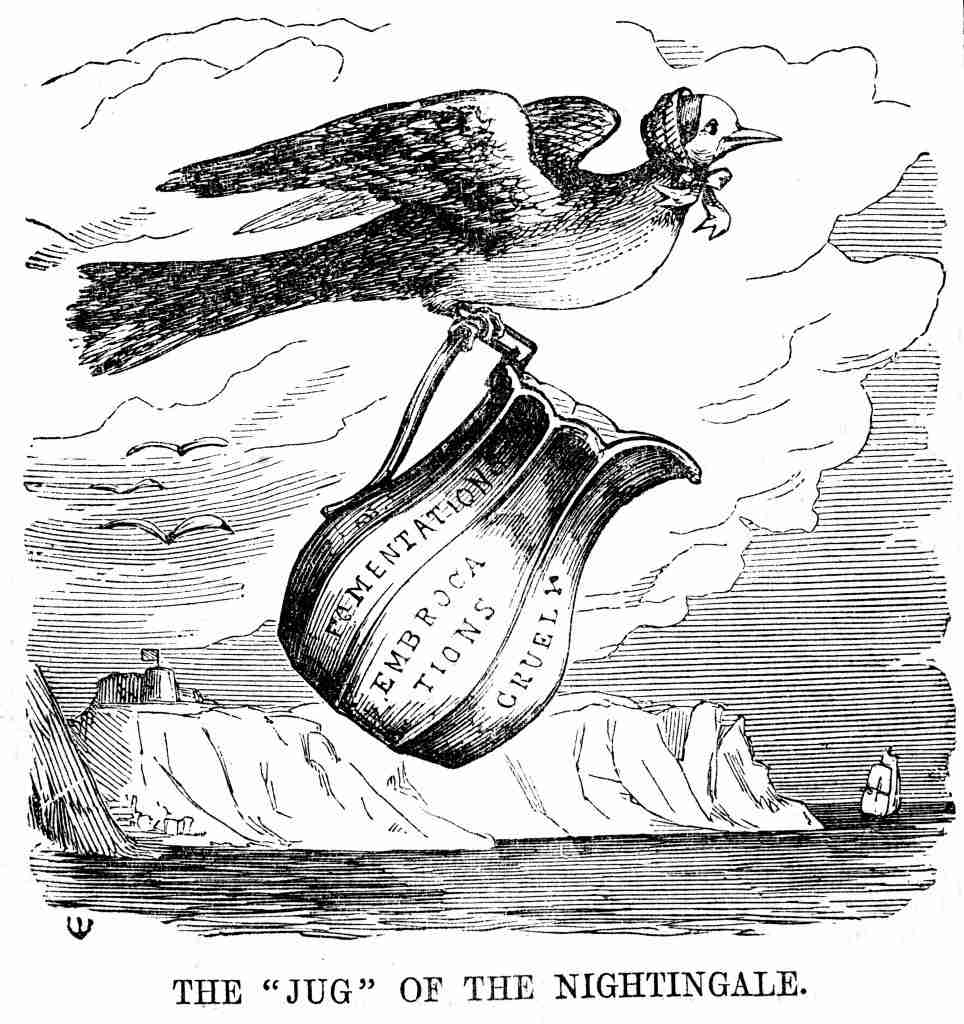

Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale, with 38 nurses, arrived at the hospital in the Scutari Barracks, near Constantinople, in November 1854. Here the wounded troops from the siege of Sevastopol, three hundred miles away, were evacuated. Many died during the journey on overcrowded ships.

Nightingale selected nurses mainly from the lower classes, whom she thought better prepared for the arduous conditions than middle class women. Despite the improved administration of the hospital and the funds she attracted, the death rate rose from 8% to 52% in two months, caused by sewage leaking into the hospital’s drinking water.

The ‘Jug’ is a reference to part of the poet John Clare’s onomatopoeic transcription of the song of the nightingale.

Rise of the riffle

Minié rifle bullet, Calibre .577 inch (14.5mm), one of which was melted and deformed on impact

Collected from Sevastopol by Dr T. E. Hale, and donated by his niece Mrs. Dugan in 1927. EUR101C

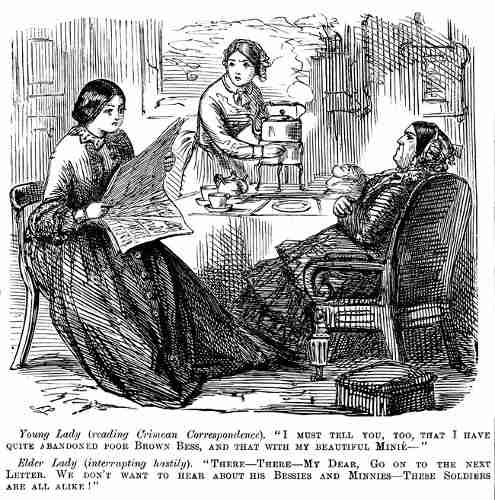

This Punch cartoon refers to the adoption of the Minié rifle, and the consequent abandonment of the Brown Bess musket, by the British army.

Designed by Claude-Etienne Minié in 1849, the Minié bullet had a concave base fitted with an iron cup. This thrust into the centre of the lead when it was fired, forcing the bullet to expand into the grooves of the rifling. It was a resounding success, allowing almost all military muskets to be converted into accurate and fast-firing weapons with greater range.

Britain adopted this system in 1851and new rifles were supplied to the Troops replacing the older “Brown Bess” muskets. These new rifles had a tremendous range, perhaps more than 1000metres, and could pass through the bodies of up to four soldiers when fired into mass ranks, thus causing a devastating effect on the enemy.

The Times correspondent at the Battle of Inkerman (1854) reported “the volleys of the Minié cleft them like the hand of a Destroying Angel”.

Russian Pattern 1845 percussion rifle was made at the Russian Imperial Arsenal at Tula. In 1853 it was modified to use the Minié bullet and to achieve this it incorporated the French “pillar breech” (systeme a tigé)

Collected from the Battle of Inkerman and donated by Major Christopher Brice Wilkinson. FA041

French Model 1846 percussion rifled carbine, dated 1850. FA034

This Pattern 1845 musket and bayonet was made at the Russian Imperial Arsenal at Izhevsk in 1846. It is almost an exact copy of the contemporary French Army musket of the period. This weapon was collected by Henry Sylvester, a young assistant surgeon at the time, who was awarded a Victoria Cross for ‘dressing the wounds and attempting to recover the wounded Lieutenant Adjutant Dyneley under heavy fire during the storming of the Redan at Sevastopol on 8th September 1855.

Collected at Sevastopol and donated by William Henery Thomas Sylvester in 1864.

FA040& EW033

This Russian Pattern 1839 musket was originally a flintlock, but was modernised in 1844 when it was converted to the percussion system. The top of the barrel has five deep sabre cut marks; the owner must have held it aloft with both hands as a defence against a mounted cavalryman slashing down at him.

FA039

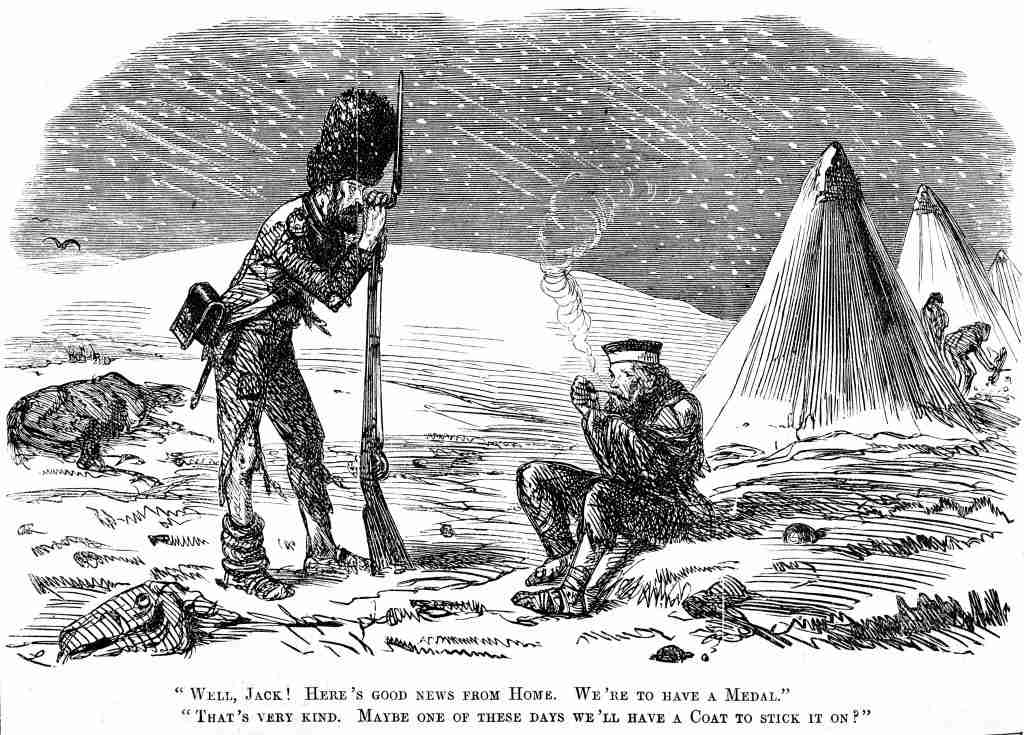

Desperate Conditions

A Crimean campaign medal was announced on 15 December 1854, just when the hopelessly under provisioned British troops were suffering the extremes of a Crimean winter, compounded by inadequate shelter, starvation rations and rampant cholera. The soldiers were still awaiting their winter uniforms, 40,000 of which had been lost by the sinking of a ship during a storm in November.

“Horses … die by the score every night at their peg from cold and starvation. Worse than this, the men are dropping down fearfully. The poor men’s backs are never dry, their one suit of rags hang in tatters about them”

Colonel George Bell, 28 November 1854.

A 6-shot percussion revolver by Clough & Sons, Bath, c.1854. This early form of revolver, known as a “pepperbox”, first appeared in the 1830s and proved to be extremely popular. Although well made there was a real risk of all six barrels being fired at the same time. When this pistol was made, John Clough’s shop was located at 9 New Bond Street, Bath.

FA005

At the time of the Crimean War British officers were required to purchase their own revolver, resulting in a great variety of weapons on the battlefield.

This 6-shot Colt Navy Model 1851 percussion revolver was made in 1853. Over 37,000 Navy Colts were produced in Samuel Colt’s factory in Pimlico, London, between 1853 and 1856. Each component of a Colt pistol, including the wooden grip, was machine made and only the minimum of hand finishing was required. This guaranteed a precise fit and more importantly the realisation of interchangeable parts.

FA024

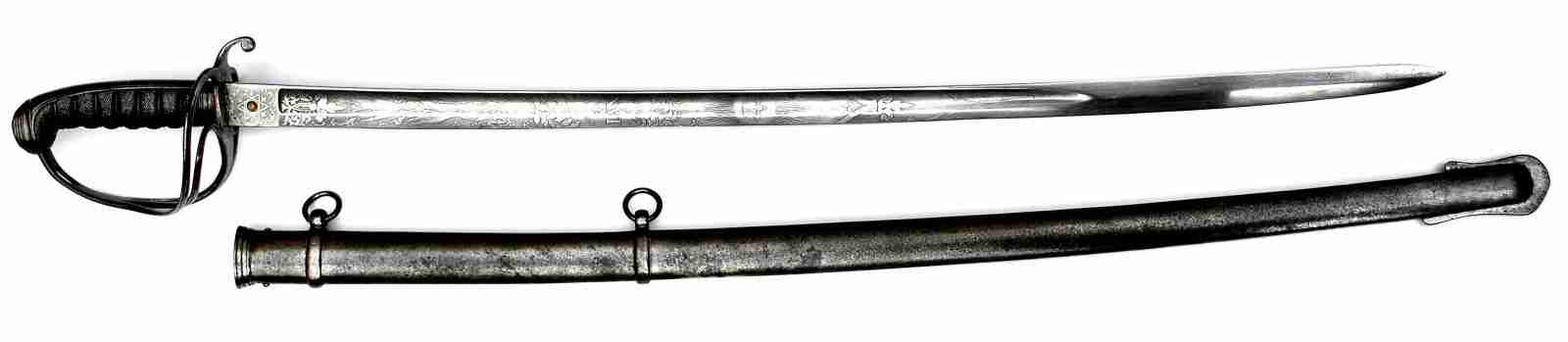

British Regulation 1822 Pattern Cavalry Sword, the type carried at the Charge of the Light Brigade.

EW002

British Regulation 1845 Pattern Infantry Officers Sword. The slightly curved single edge blade is decorated with an etched pattern of foliage incorporating the Royal Cypher VR. It has a half-basket hilt of gilded brass formed with the Royal Cypher VR and the shark-skin grip.

EW003

A British “Lancaster” Sappers & Miners sword bayonet by R & W Aston, Birmingham. The distinctive blade is Falchion or spear shaped.

EW032

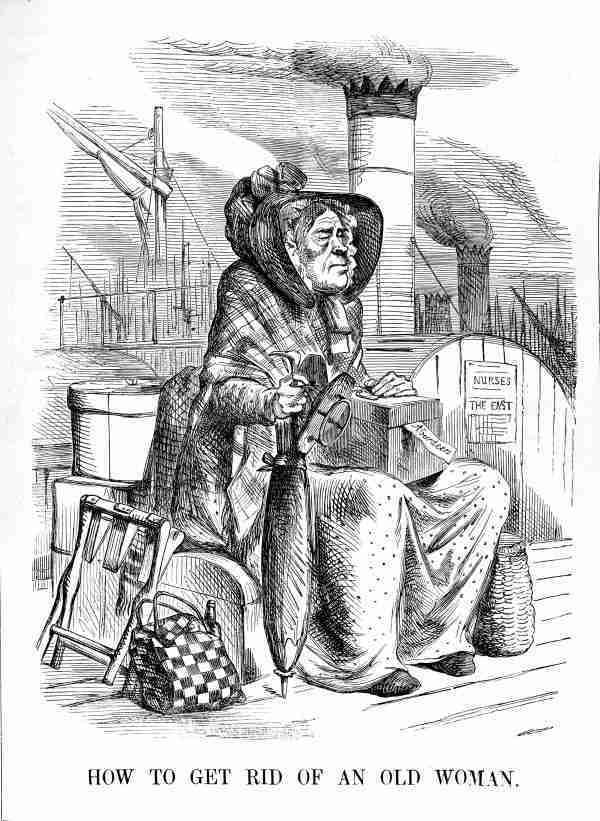

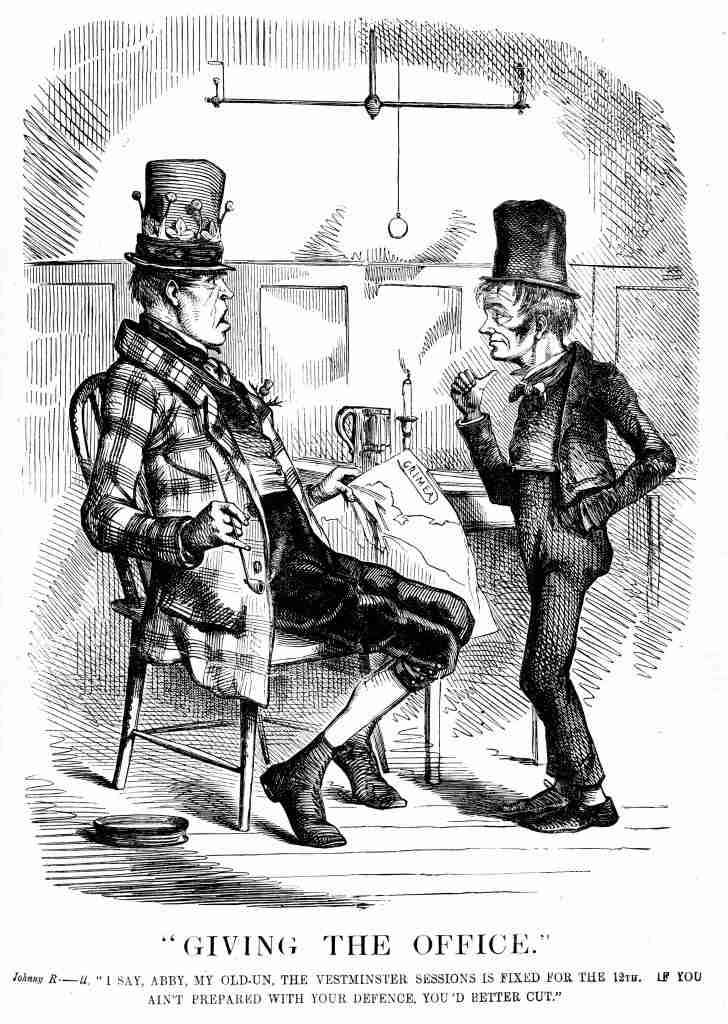

Political Crisis

John Russell, who resigned his post as Foreign Secretary before the start of the war over his frustration for the Prime Minister’s lack of support for Turkey, here warns of the new session of parliament, starting on 12 January 1855. A robust media campaign was increasing the pressure on Aberdeen to attend to the shameful condition of the troops in the Crimea.

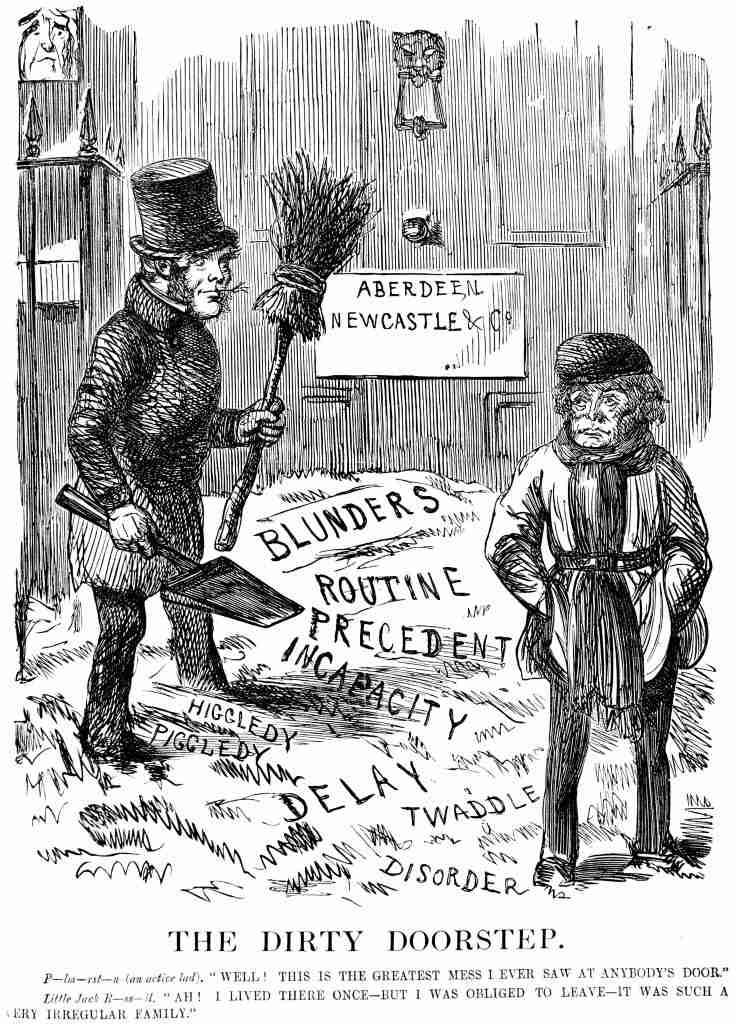

Two weeks later the Prime Minister resigned, following a debate in parliament which he considered a vote of no confidence in his leadership. A week later the Queen asked Lord Palmerston to form a government, and here he is, cleaning up the mess at No.10 Downing Street.

Teams of nurses were arriving to care for the wounded in the Crimea. In this cartoon Punch makes a cruel double pun, with Prime Minister Aberdeen being dispatched as a nurse to the Barrack Hospital at Scutari.

The aggressively military Palmerston was already popular with the English press and was widely expected to bring the war to a swift and decisive victory.

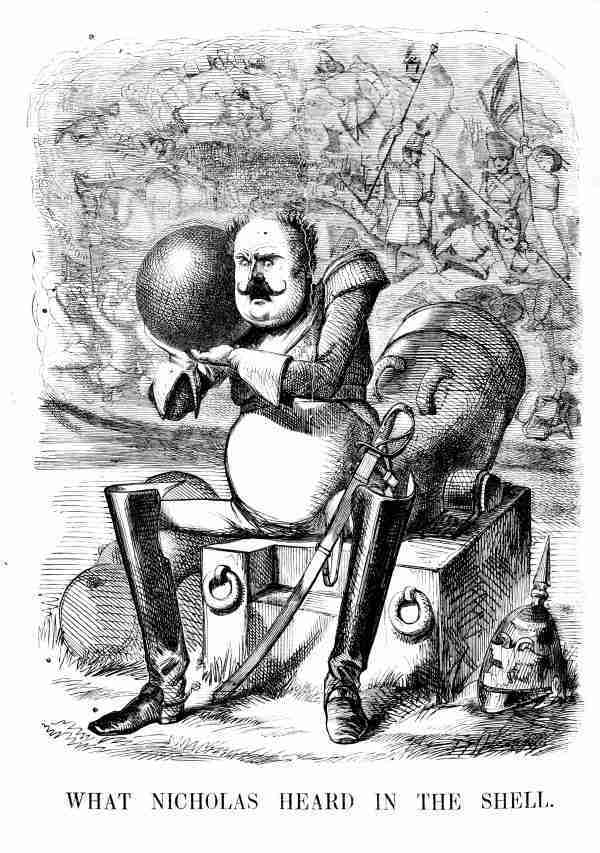

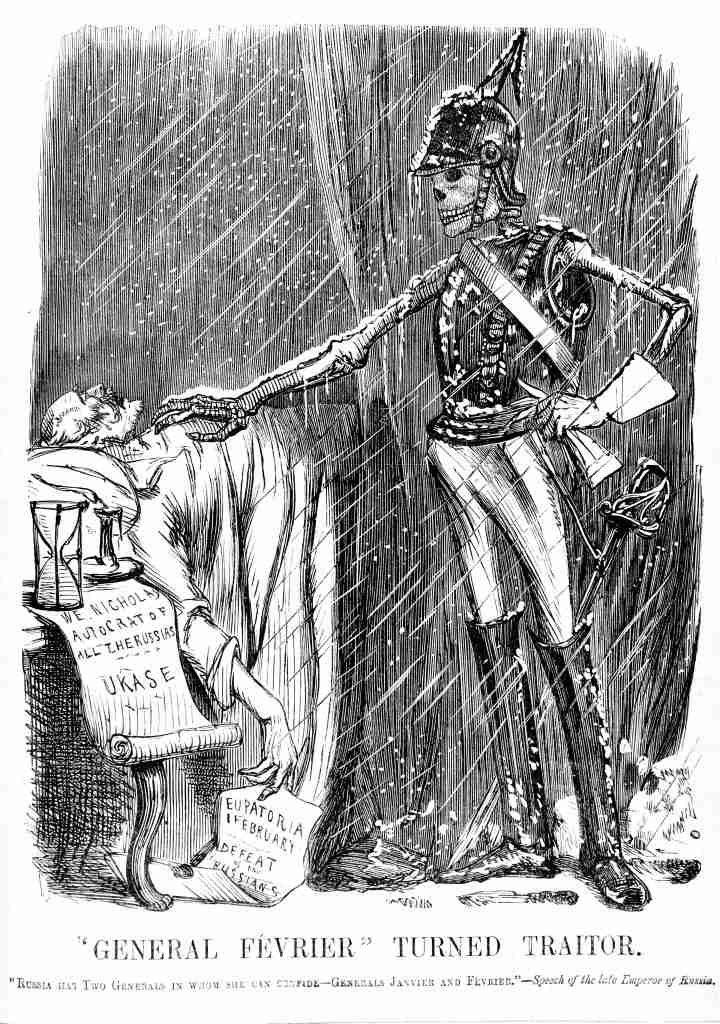

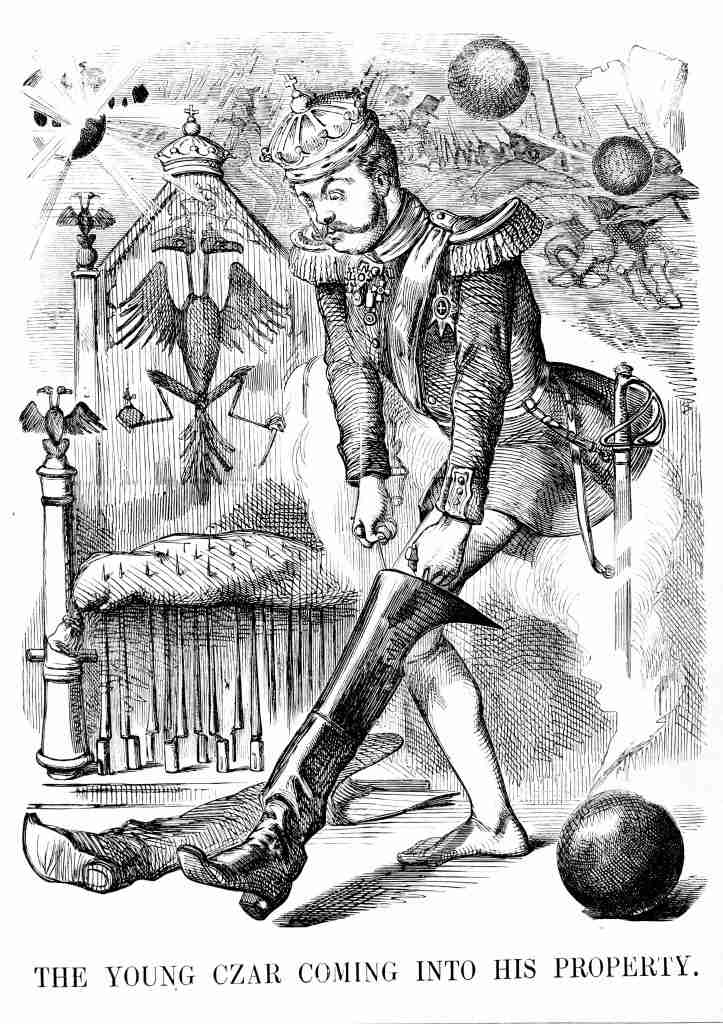

With the death of Tsar Nicholas, there was an expectation in Britain and France that Russia might sue for peace; this was also the hope of many Russian officers. However the new Tsar, Alexander II, was not willing to act in a manner which either dishonoured his father’s wishes or humiliated Russia.

In November 1854 Tsar Nicholas I had talked of having ‘two Generals who will not fail me: Generals January and February’, alluding to the belief that the winter played a decisive role in the defeat of Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia. Two months later he was suffering poor health and increasingly despondent about the direction of the war. After conducting a review of troops in St. Petersburg in freezing conditions, he caught pneumonia. A disastrous Russian military failure at Evpatoria, carried out on his direct orders, deeply affected him and he died shortly after on 2 March 1855.

Fall of Sevastopol

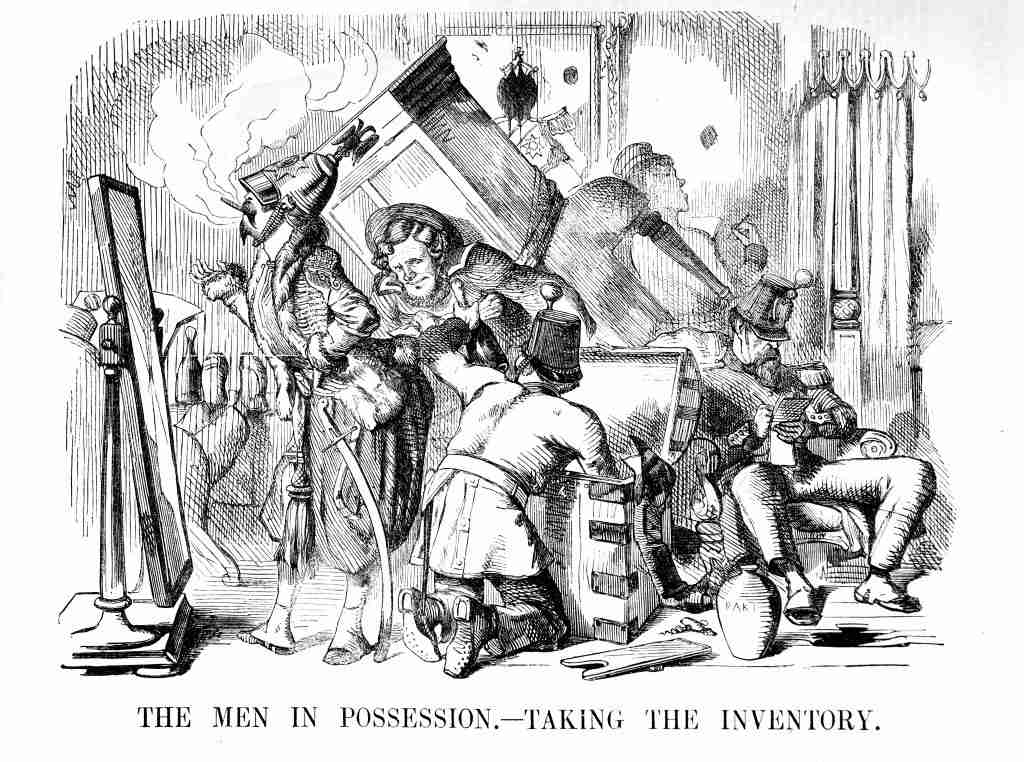

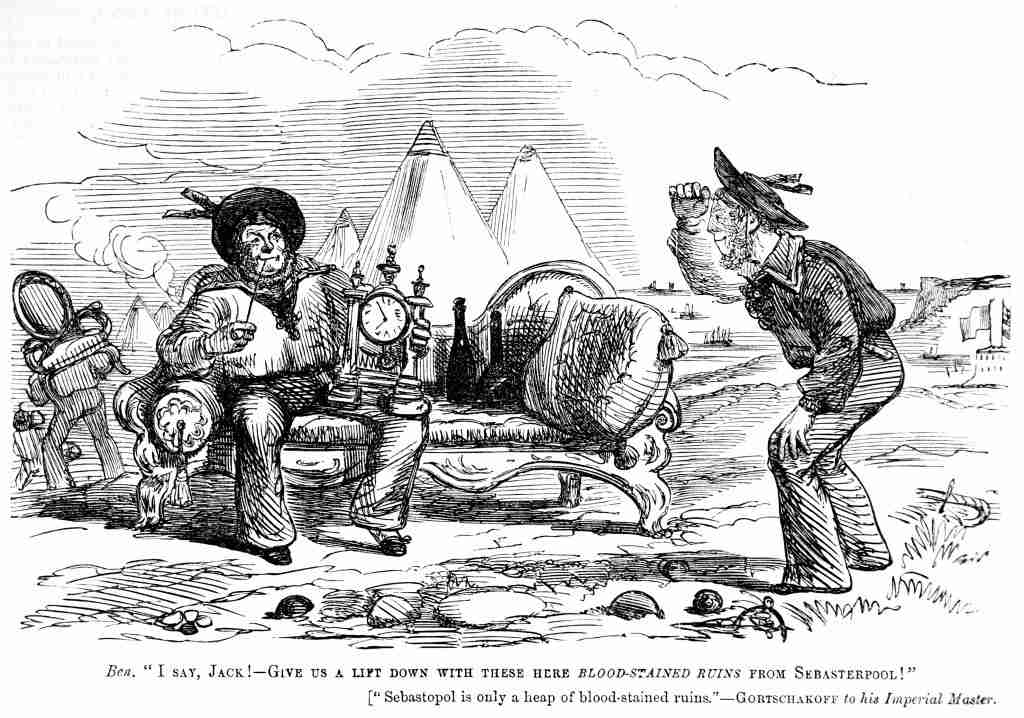

Throughout most of 1855 the siege of Sevastopol was in stalemate, with neither side making successful advances. Eventually the Allies built a railway to supply ammunition and provisions to their entrenchments; this facilitated a brutal bombardment, peaking at 400 shells a minute, resulting in a horrendous loss of life. The town was finally taken in mid-September, intentionally set alight by the Russians as they left.

These cartoons make light of the whole affair, showing the plundering of well-appointed houses which lasted for more than a month. By the end of the siege General Gorchakov reported ‘Sevastopol is only a heap of blood-stained ruins’.

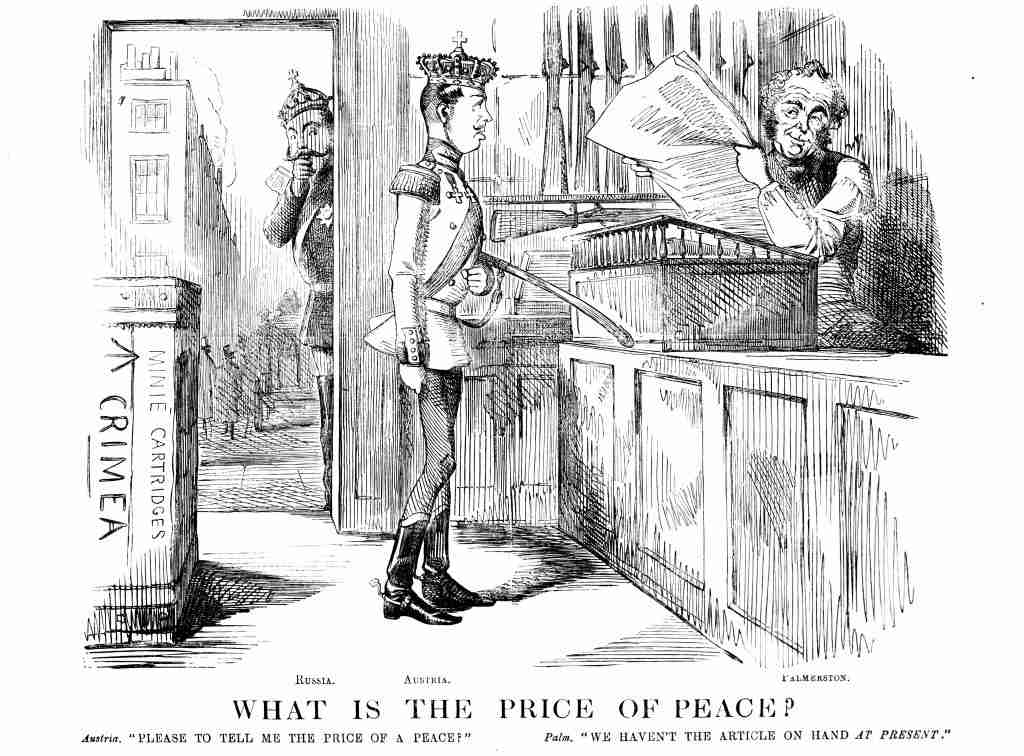

Peace: Reluctance and enthusiasm

While Austria and France began peace negotiations with the Russians in late 1855, Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister, was still intent on continuing the war. He felt that it was vital to avoid an unsatisfactory peace which would leave unaccomplished the real objectives of the war. These he considered were ‘to confine the future extension of Russia’ by promoting internal unrest to break up the Russian Empire from within.

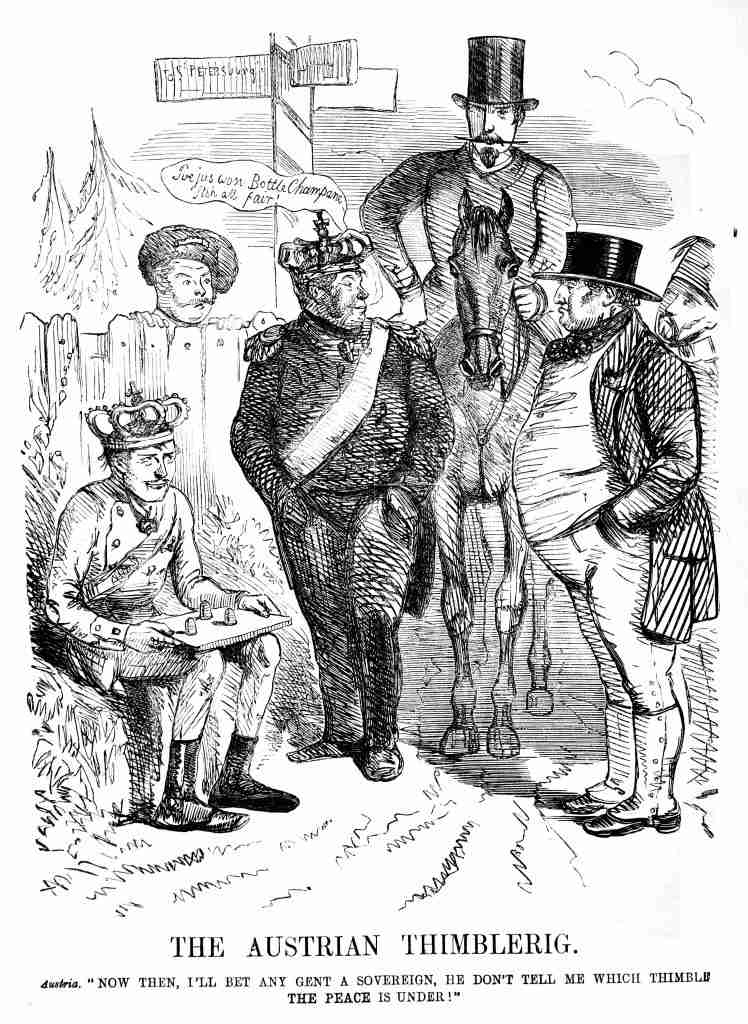

Austria is depicted as a confidence trickster, with Prussia acting as the stooge, and France, England, and Turkey as the intended ‘marks’; Tsar Alexander peers nervously over the fence.

Austria had presented Russia with an allied ultimatum and Russia had accepted with some modifications. However, as these modifications were not in its favour, Austria threatened to break off relations with Russia.

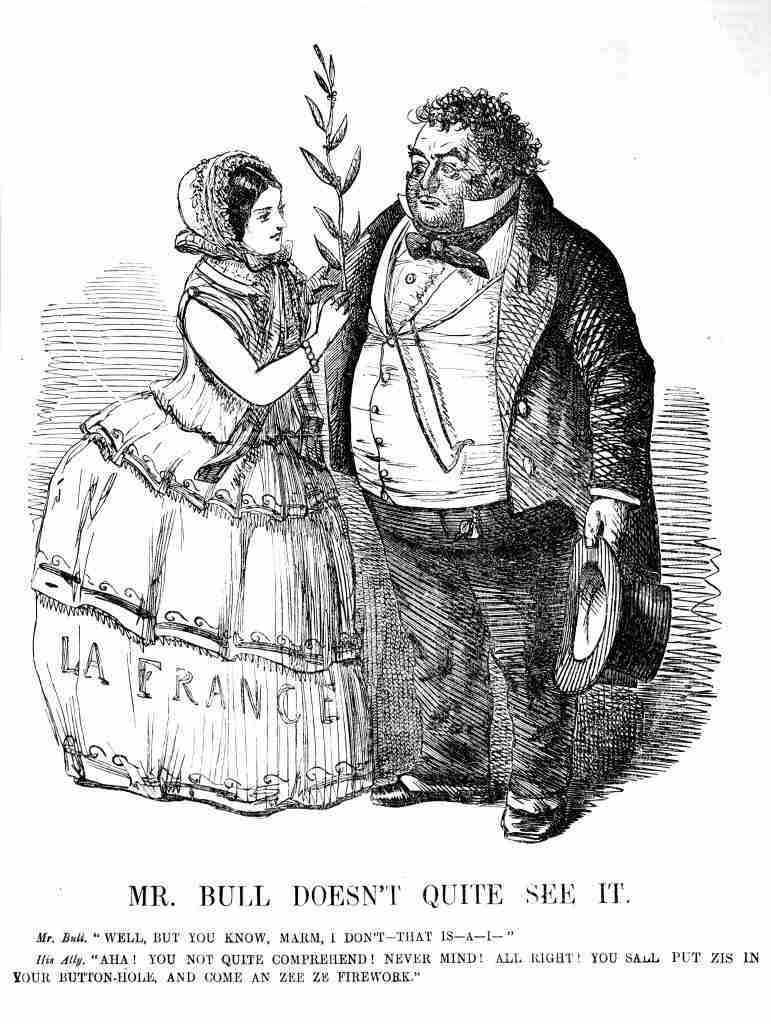

Peace was eventually negotiated over five days in February 1856, at a congress in Paris. The agreement was much along the lines of proposals set forth before the war by the allies, with the Turkish Ottoman Empire retaining its independence and territorial integrity, though both Russia and the Turks were denied the right of maintaining a military presence in the Black Sea. Celebrations were held throughout Britain and France during May, though in this cartoon John Bull, Britain personified, remains sceptical that there is anything to celebrate.

Royal Albert Memorial Museum

In 2019 the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, kindly transferred a small collection of artefacts they held relating to the Crimean War to the BRLSI Collection. While those objects were not included in the 2012 Crimean Relics exhibition, we are sharing them here for your interest.

Russian Imperial short sword (also known as a sidearm) from the Battle of Inkemann. Stamped on both sides of the ricasso with ordnance marks, including the Cyrlic letter Џ (D). Brass ribbed hilt and cross-bar with ordnance marks and the date 1847.

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

Originally donated in 1874 by Alfred G. Paul.

EUR601

Belt for 29 paper cartridges used in a muzzle-loading gun. The cartridge holders are made from leather, moulded and stitched on with yellow thread and with a crimson velvet flap to keep the powder dry, and velvet pockets or pouches stitched on. Caucasus, perhaps Turkish, c.1840.

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

EUR602

Large artillery powder horn for priming cannons. Horn body with suspension rings, at one end a brass charger with spring cut-off; other end with a wooden stopper covered with a brass cap. Removable screw-out wooden disc-shaped filling peg. Probably Russian c. 1840.

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

“taken at Sebastophol” – originally donated by W.J. Harvey.

EUR603

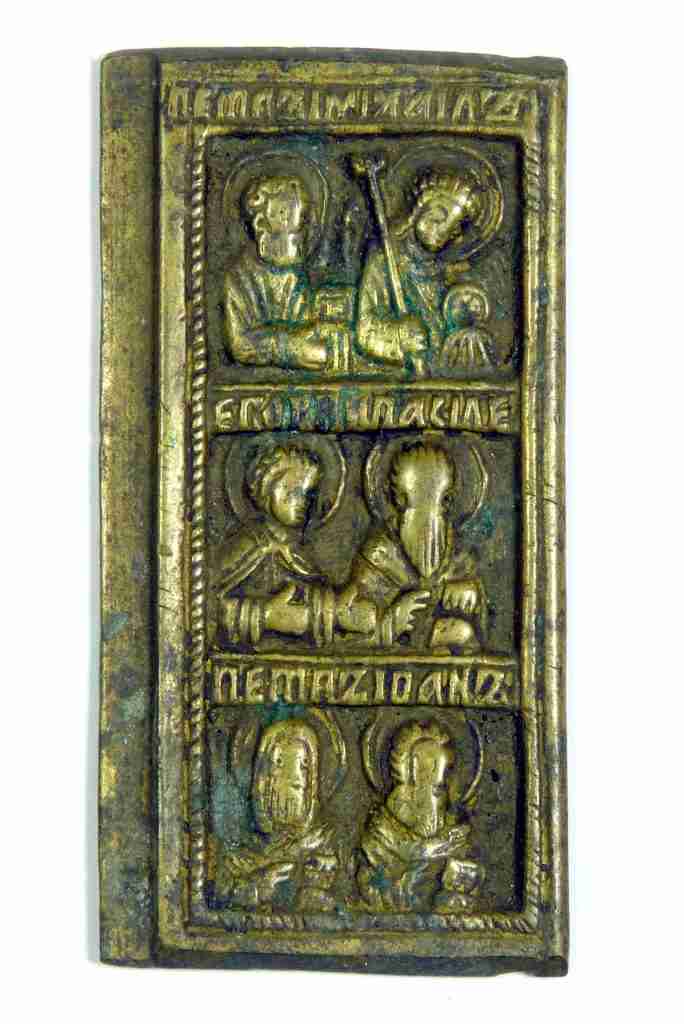

Russian Icon with 3 panels depicting saints.

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

EUR604

Small cast brass crucifix, the outer edges with Cyrlic script. Top of cross broken off and missing.

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

EUR606

Carved wooden pipe in 2 pieces, sections attached to one another by a cord of red and yellow thread, with a small ‘stick’ attached, perhaps for cleaning or tamping down the tobacco.

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

“taken after the fall of Sebastopol” – originally donated by P. Silvester.

EUR605

Button made from a Russian 2 Kopecks, standard circulation coin of Catherine the Great, 1764-1780. Obverse: Crowned monogram of Empress Ekaterina II within wreath. Lettering: Е II; К М. Reverse side: Value, date in crowned cartouche, two sable. Lettering: СИБИРСКАЯ ∙ МОНЕТА ∙ + ∙ ДВЕ КОПЕ ИКИ∙ 1769 (partly obscured by soldered on loop). Translation: Siberian coin, Two Kopecks; КМ – Suzun Mint (“Kolyvan copper”).

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

EUR607

Iron cylindrical padlock

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

EUR609

Russian icon fragment

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

EUR610

Pair of iron stirrups

Transferred from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 2019 and incorporated into our own larger collection of items related to the Crimean War.

EUR608

Credits

Curated, researched, written, and laid-out online by Matt Williams, Collections Manager, BRLSI

Original design and curatorial support, Jude Harris

Proof reading, Rosemarie Davies

Weaponry specialist advice, Brian Godwin

Digitisation, Matt Williams and Brian Godwin

French translation, Jeremy Martin