Why does the Institution have so little Roman material in its collection?

The BRLSI Collections stores don’t hold many Roman artefacts. This impressive enameled brooch from Lansdown is an exception, as are the stone coffins in the courtyard.

Yet many Roman objects came to light as medieval Bath was torn down during the Georgian building boom. They were at first handed to the city but, once this Institution was founded in 1824, they came to us and were the basis of a significant collection of Roman pottery, jewellery, metal work and sculpture.

Where have they all gone?

Some of these items were deposited at the Institution, then the de facto city museum, by the City Corporation, having been given to the city, others were donated directly to the Institution Collections. When the Roman Baths became a museum in 1897, Roman objects belonging to the City were transferred there for storage, conservation and display. More things joined them there on loan from us the 1960s when the Institution was going through difficult times.

The Roman Baths now has a significant collection of Roman objects and many of the important relics on display there were either once deposited with, or are on loan from, the Institution.

Roman Bath on display at the Roman Baths Museum

These are just a few items from the BRLSI collection on display at The Roman Baths, mostly in the Living in Aquae Sulis Gallery (with thanks to Collections Manager Zofia Matyjaszkiewicz for the images):

What else has left our collection?

Many items, some in urgent need of conservation, were dispersed to other local museums in the past. Many of these collections are now formalised as loans from the Institution.

- ancient Egyptian relics to Bristol Museum

- Jurassic ichthyosaur fossils to the National Museum of Wales

- a number of paintings to the Victoria Art Gallery

- in addition, many books were sold by the Council in the 1960s when the Institution was not operating

What remains with us today is thanks to the strenuous efforts of a few dedicated volunteers in the latter half of the 20th century.

Things that disappear over time

The survival of objects through history is precarious. Museums aim to serve as a safe repository, but even this can’t be guaranteed.

The story of the ‘missing’ head – two accounts from the Institution’s library

1. Rev Richard Warner ‘The History of Bath’ 1801

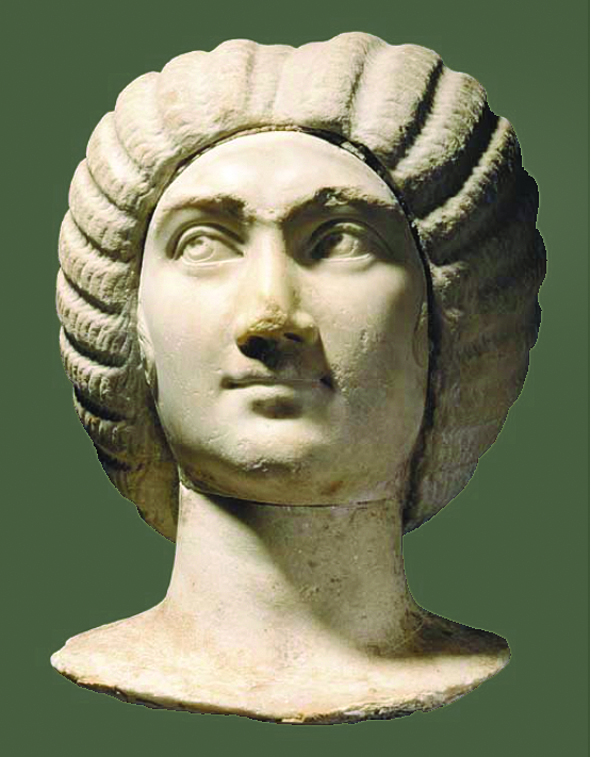

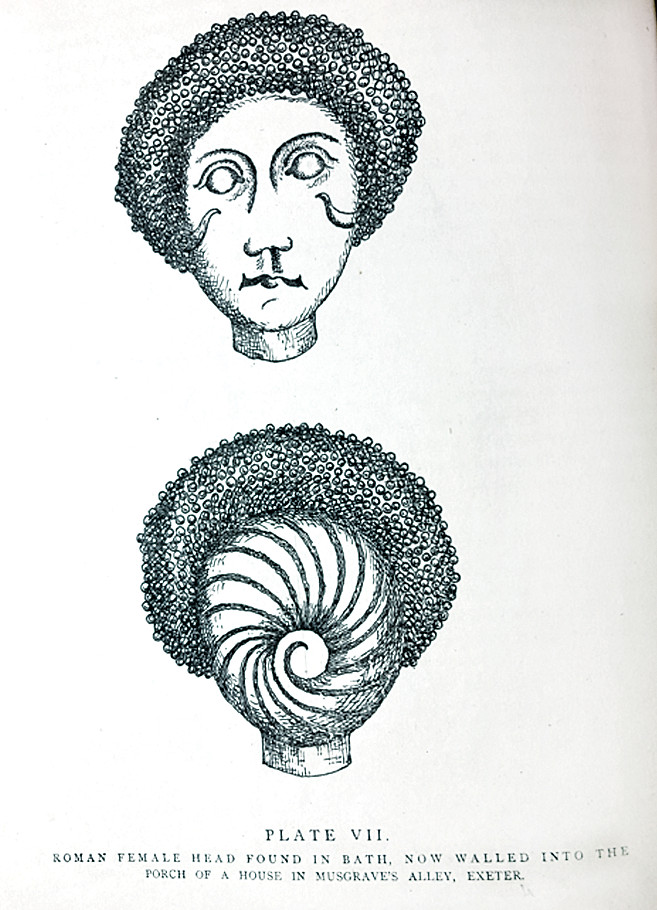

Warner writes that the ‘bust of a female figure’ was discovered in Bath in 1714 and was being held in ‘a private collection’. It is illustrated in his book, but he is chiefly intrigued by the hairstyle, finding a similarity to the fashionable preoccupations of the women of his own time.

Strangely he fails to mention the size of the head, which was later estimated as once belonging to a statue over 3 metres high.

2. Rev H. M. Scarth, ‘Aquae Solis, or Notices of Roman Bath 1864

Some 60 years later, Reverend H. M. Scarth, referencing Warner’s account, describes it as a ‘Colossal female head’. He gives us more information about its discovery and fate, though he doesn’t mention actually seeing it himself and probably copied the illustration in Warner’s book.

He says that soon after its excavation in Bath, it was sent ‘as a present’, to Dr Musgrave (an eminent 18th century antiquarian) who lived in Musgrave’s Alley, Exeter. Some years later it became into the possession of the next occupant of the house, a solicitor, who built it into his wall in such a way that it displayed both front and back of the head, revealing all the detail of its elaborate hair style. The porch was destroyed in the 1870s and the fate of the head is uncertain.

Scarth comments “It is much to be regretted that it has passed out of the city of Bath, as it ought to form part of the Collection of Roman Antiquities in the Literary and Scientific Institution.”

Footnote: this head has been identified as being of Julia Domna (170-217AD), a Roman Empress celebrated for her political and philsophical influence, and the mother of Caraculla. She is shown in her portraits wearing very innovative and elaborate hairstyles, which have been recreated by a hairstyle archaeologist, Janet Stephens, in several online videos.